Memes have been increasingly used as a medium of resistance and dissent in the online publics. Meme culture has enabled new forms of political participation by supplementing collective action and social movements.

While allowing multiple, vibrant voices to contribute to the political discourse, memes have also been appropriated by political parties and corporations as propaganda and marketing tools, eroding their democratic power.

By analyzing the origins of memes, their politicization, their current uses, and their relationship with the state, this article highlights the importance of harnessing the power of memes to initiate greater political action.

The term ‘meme’ was first coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene. Derived from the Greek root ‘mimema’ (imitated) and used as the cultural analogue to the concept of ‘gene’, Dawkins refers to a meme as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” that spreads from person to person. He compares genetic propagation through reproduction with memetic propagation through imitation, and shows how these concepts play out in the evolution of clothing/fashion, the passing down of skills, and the propagation of religious ideas. In the years following the release of the book, there was much academic debate and discussion around the meaning of the term. It was only with the advent of the internet that the word entered common parlance. Today, it is colloquially used to refer to internet memes, which ‘Meme Librarian’ Amanda Brennan defines as “pieces of content that travel from person to person and change along the way”. Internet memes are not merely imitations, they are mediated, and actively acted upon, by people who may modify or use them to advance certain arguments. There are several definitions of what constitutes an internet meme, but Brennan underscores its multimedia nature and emphasizes the participatory aspects of meme culture by positioning people as the agents of change. Digital media scholar An Xiao Mina categorizes memes into image memes and image macros, text memes (e.g. hashtags), video memes (such as GIFs), physical memes, performative memes, and selfie memes (a sub-genre of performative memes). Irrespective of their form, memes express opinions, take stances, and engage in meaning making. They are produced through remixing, use of intermemetic references, derivatives, juxtapositions, parody, satire, etc., and are diffused rapidly via online social networks.

Memes are increasingly also used as a medium of resistance and dissent while simultaneously being appropriated by political parties and corporations who have the necessary resources to do so at their disposal.

Internet memes have been commonly viewed as humorous, playful media texts, ‘inside jokes’ made by and for specific groups of people online who share similar interests. However, memes are increasingly also used as a medium of resistance and dissent while simultaneously being appropriated by political parties and corporations who have the necessary resources to do so at their disposal. This may erode the democratic power of memes. So, how can memes be used to shift dominant socio-political narratives? What is the growing role of meme culture in collective action, and how can memetic strategies supplement social movements?

The Origins of Political Memes

The use of short, succinct messages that assert a political standpoint and thereby trigger conversations and debates is not a new phenomenon. Some view memes as the street art of the digital landscape, others see in them an extension of the political poster culture common in India. It is, however, not the visual nature of memes that elicits these comparisons, but rather their participatory nature. Members of opposing political outfits often produced spoof posters as a way of engaging in localized political turf wars. The democratizing nature of the internet has now opened up avenues for regular internet users to contribute to this culture. Memes serve as a medium of information directed primarily at younger people, inviting them to participate in political discussions. Furthermore, what counts as political participation has evolved and expanded in the digital era. Voting in elections or becoming a registered member of a political party are no longer the only means of political participation. Engaging in political conversations online, posting and re-posting information, and amplifying political standpoints through memes are other modes of political participation increasingly used in the digital era. The multimodal and participatory nature of meme culture creates a more active and engaged form of polyvocal citizenship in which multiple, vibrant voices and opinions contribute to the political discourse.

Memes are not just products of human agency and creativity but are also tied to the local contexts in which they are created. Thus, the larger socio-cultural and political milieu in which people and communities exist has a bearing on the production, quality, and content of memes as people infuse a bit of themselves in the memes they create and circulate. Through collective and connective action, memes are used by organizations and individuals to initiate political action. Collective action, usually engaged in by advocacy groups and non-governmental organizations like Greenpeace, requires a significant amount of resources and mobilization of people. In connective action, a term coined by academics W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg, individuals voluntarily share personalized content across fluid media networks that they are part of. While the internet has certainly widened the scope of collective action, its core principles have remained the same. However, connective action has prevailed in the face of authoritarian policing of citizen’s collectives and the narrowing scope of civil society organizations. The hashtag #PrayforNaesamani, for instance, was made viral through connective action as people without any political background or organizational affiliation turned a pop culture joke into a political statement.

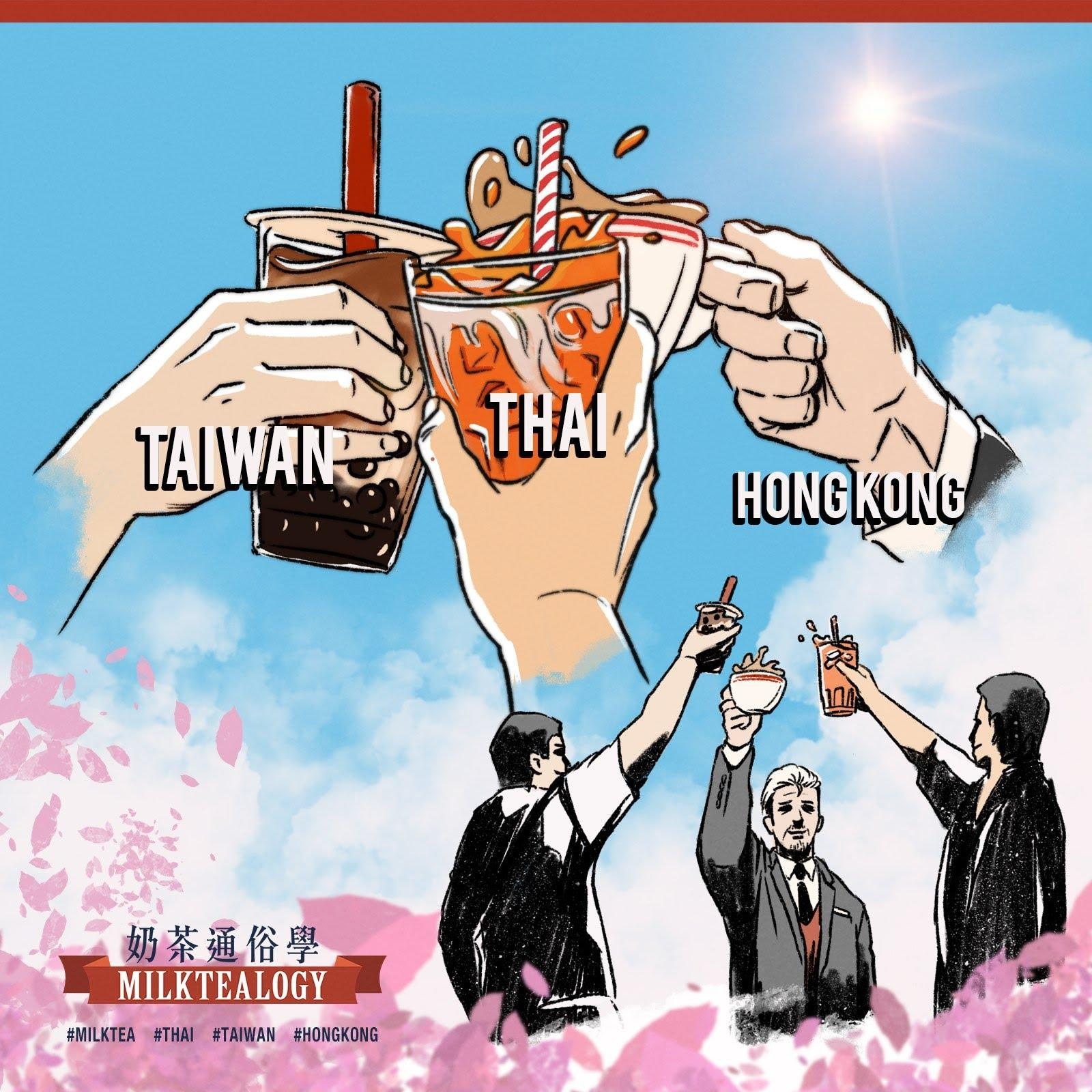

Our networked societies and their resultant connectivity also help memes travel across borders. It is this transnational nature of meme culture that turned a meme war into the pan- Asian, pro-democracy #MilkTeaAlliance and inspired Indian police officers to use the popular Ghanian dancing pallbearers meme to spread awareness about Covid-19.

The meme that inspired the Milk Tea Alliance (Source: A Facebook page called Milktealogy)

The meme that inspired the Milk Tea Alliance (Source: A Facebook page called Milktealogy)

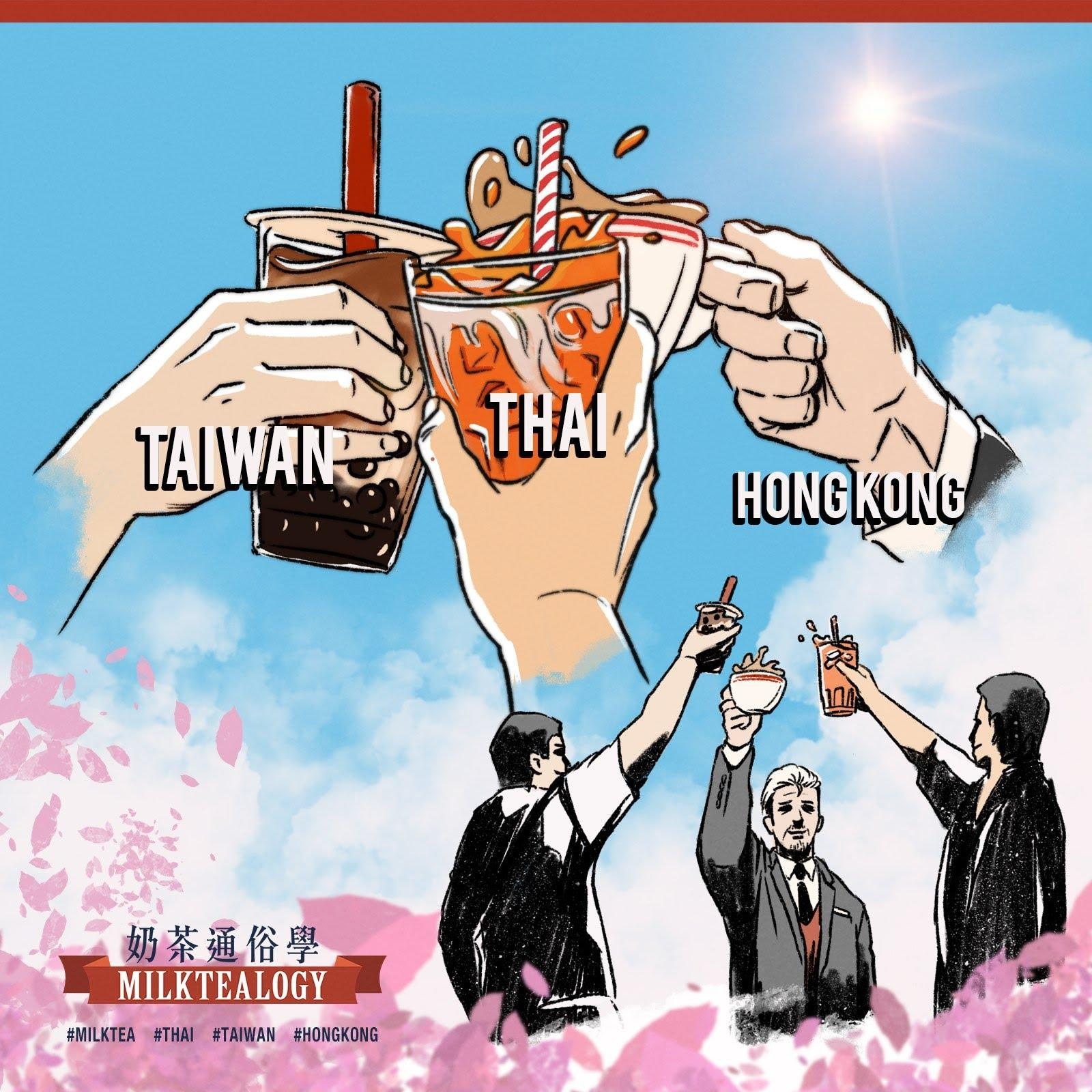

A derivative of the poster including more countries in the alliance.

A derivative of the poster including more countries in the alliance.

How are Political Memes Used?

Memes, whether political or otherwise, are fundamentally about expression. They are also used as a means of establishing relatability with others. Finding and connecting with others who share similar political ideologies, and building a community around shared ideologies can be curative for some. Since memes reflect current realities, they can reaffirm feelings of outrage, helplessness, and hope. Memes also make it easier to creatively indicate political allegiances and affiliations. As short, and usually visual, media texts that cleverly contextualize an issue while simultaneously taking a political standpoint, they are especially effective within the attention economy.

Narrative Building

Academic Anastasia Denisova refers to memes as “units of persuasion”, the circulation of which serves as “symbolic ideological negotiation” and helps spread the core message of a group in online networks. Memes have the ability to realign political discourses. They can be empowering for marginalized groups seeking to shift the narrative in favor of the causes they espouse.

Every major event creates a number of commentary memes that are, over time, remixed with other memes and pop culture references. Participants of online social movements are often inspired by, borrow from, and respond to memetic discourses that have preceded theirs. This is effectively done through the use of templates that build on existing and familiar ideas and concepts. For instance, #BlackLivesMatter (#BLM) served as the template for the #DalitLivesMatter which highlighted systemic caste-based oppression in India. At the same time, Indian celebrities endorsing #BLM were called out on social media for remaining silent about atrocities against Dalits in India. They were accused of engaging in performative activism and virtue signaling through memes. And, just as people with different (predominantly right-wing) political affiliations in the US countered the #BLM with #BlueLivesMatter and #AllLivesMatter, in India the #DalitLivesMatter hashtag was appropriated by right-wing groups into #HinduLivesDontMatter.

Around 2014, posters created by the publisher Indian Book Depot (Map House) were being used as a template to convey diverse and often opposing political stances and narratives. The posters, conceived around the figure of an Adarsh Balak, or an ‘ideal boy’, were common till the 1980s as an educational tool. The derivative posters, which were shared widely online, used the Adarsh Balak template to create memes that engaged with themes of morality, ethics, feminism, and a whole range of social issues. It was first adapted by Mumbai-based artist Priyesh Trivedi who retained the vintage aesthetics of the older posters but added his own subversive dark humor, thus overturning the original concept of the ‘ideal boy’ through parody. In this new iteration, the ‘ideal boy’ was shown engaging in activities (such as drinking and smoking) that reject societal norms and narratives of ‘ideal’ behavior (such as helping strangers and being respectful to his parents), as portrayed in the original posters. The template created by Trivedi was later remixed by art school students to create a satirical take on the ‘bad girl’ in which having breasts, pouting, and riding motorbikes were ironically framed as traits of being ‘bad’. Other derivative posters took potshots at right and left-wing ideologies, and were used in online meme wars. By keeping the aesthetics of the India Book House (Map House) posters intact, the Adarsh Balak memes created a ready audience in those who recognized these posters with a nostalgic familiarity, and then leveraged their attention to shed light on contemporary socio-political issues while ensuring some degree of virality.

Even though the neo-liberal appropriation of social movements borders on the performative, it can also foster new connections in digital and physical spaces and lead to civic action.

While the Adarsh Balak memes drew from the offline world, online memes can also make their way into the physical world. Resistance movements have often creatively used memes in offline spaces. In India, the nationwide protests against the controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) in late 2019-early 2020 saw overwhelming participation from young people and university students who adapted and leveraged existing memes as one of several modes of protest. Remixed versions of common meme templates such as “OK Boomer” and “Does it Spark Joy?” were often seen at protest sites. Memes have also made their way into physical objects. Everything from mobile phone covers, bags, and t-shirts have memetic images or phrases, and signal a certain stance on socio-political events. Even though this neo-liberal appropriation of social movements borders on the performative, it can also foster new connections in digital and physical spaces and lead to civic action.

The fluidity with which memes travel between different spaces marks a convergence of old and new forms of media used together in creative new ways. For instance, #PrayForNaesamani turned a scene from a film into a trending hashtag, and online posters generated by the meme later appeared on t-shirts and caps in the physical world.

Community Building

Memes can also simplify complex political discourses or make them more palatable through humor and emotion. They act as conduits of political expression, offering affective affirmation regarding an issue, and help reach out to others with similar political ideologies. This aspect of memes helps build camaraderie and solidarity in online publics.

In memes that use pop culture references, the ability to recognize the reference, see the humor and/or sarcasm embedded in them, and understand the intention of the meme-maker can be a form of community building. The fact that a group of people find something funny and interesting helps create a sense of collective or shared identity. This method of leveraging shared identity by using local pop culture references to draw attention to a cause is often used in the southern Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. The #PrayForNaesamani trend was, at least partially, intended to confuse non-Tamil Twitter users. The confusion, and the curiosity that no doubt followed, was part of the process of drawing attention to the meme and the accompanying hashtag. The use of Malayalam movie references to express dissent against Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah could be read as a deliberate attempt to call out their ignorance of local cultures and languages, thus exposing their narrow, North-India-centric politics.

It is also not a coincidence that the #PrayforNaesmani hashtag started in the state of Tamil Nadu which has historically resisted the BJP’s overtures and where the party failed to gain a single seat in the 2019 elections. What started as a humorous response to a question posed on the internet turned subtly political. “Praying” for Naesamani’s health was a cathartic experience and a moment of pride for a state which had rejected Modi in a departure from the national political trend. As such, this meme hashtag is a great example of what An Xiao Mina calls the “affirmation superhighway” – a take on the metaphor of the internet as the ‘information superhighway’. As an affirmation superhighway, the internet is used to affirm one’s political beliefs, values, standpoints, and identities especially by leveraging the emotive nature of memes. Mina writes that the internet is inundated with “feelings” and memes take on the role of being “vectors” of these “feelings” that enable “people to find and affirm each other”. Fundamentally social in nature, meme culture offers a steady flow of affirmation through repetition and reiteration. Within its scope, humor and outrage are not experienced in isolation. Instead, these emotions are socially validated.

State Propaganda, Censorship, and Circumventions

Memes no longer inhabit only niche corners of the internet. Celebrities, corporate houses, and political parties now use them to further their messages. The Delhi elections in 2020 witnessed a slew of meme wars on Twitter, with some political parties proving themselves more adept at using this format than others. Elsewhere too the reiterative capacity and participatory nature of memes is being increasingly appropriated by political parties to offset criticisms against the state. Employing memetic tactics to bombard people with their political messaging, governments around the world have attempted to stifle dissent and build pro-government narratives. Memes are also used to display public support for the state, its ideologies and policies, through the number of shares and likes that pro-government memes accumulate. They are the new tool in the arsenal of the propaganda apparatus of many authoritarian states.

Furthermore, propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation is spread via peer-to-peer networks that people trust over more mainstream sources. Overwhelmed by the amount of information they receive, people rely on heuristic shortcuts, placing their trust on ‘who’ sends them the information rather than verify the source. Through atomized targeting of users on social networks, those who are already susceptible to accepting mis/dis-information are identified and targeted with affirmative political messaging. This is particularly dangerous when the playful vernacular of memes is used to reinforce and exacerbate existing social hierarchies by denigrating, repressing, and othering marginalized voices.

The use of memes by political parties which have a disproportionate amount of resources at their disposal, undermines the democratic nature of memes and tilts the balance towards the powerful. Additionally, the state also uses every possible legal avenue to silence free speech by cracking down on memes created and shared by citizens.

However, the very nature of memes makes censorship difficult. Dynamic and ephemeral in nature, memes constantly change as they spread. Always a work in progress, there is no ‘final’ form that a meme takes due to contextual repurposing and overwriting. Since they are a collective exercise, memes are also tough to attribute to a single author or creator. Memes that take the form of parodies and mash-ups have the added ability to circumvent censorship. By using pop culture references, meme creators navigate the fine line between outright criticism and silly, absurdist humor. By leveraging iconic dialogues from popular films, citizens get to ‘say’ things to their elected representatives which would otherwise get them in trouble. Since memes often take the form of movie scenes inter-cut with footage from political rallies and TV interviews, they are harder to censor. As professor Ethan Zuckerman argues in his “Cute Cat Theory”, censorship of digital social activism by the state also inadvertently censors the more amateur, user-generated content online (like pictures of cute cats), thus upsetting more people than was originally intended. By making space for the ‘silly’ memes, the continued existence of the ‘serious’ ones is safeguarded. An Xiao Mina builds on Zuckerman’s theory further and argues that the ‘silly’ has often been used to express the ‘serious’ ideas through the tactical use of puns, images, coded language and in-jokes that circumvent precise censorship methods (such as those used in China). In fact, the humor and ‘frivolity’ embedded in memes also increase their shareability across platforms and spaces, once again making censorship difficult.

Laughing at someone or something can be a way of destabilizing or even subverting entrenched power relations; who laughs at whom, how many people join in, and how the person being laughed at reacts have much to say about the complex navigations of power.

Humor is akin to a digital analgesic, and advances the core argument of a meme, notes media communications professor Bradley Wiggins. Humor, particularly when used to convey a sense of irony, questions authority and political omnipotence, and demystifies power and the facade of competence. Laughing at someone or something can be a way of destabilizing or even subverting entrenched power relations; who laughs at whom, how many people join in, and how the person being laughed at reacts have much to say about the complex navigations of power. Ironic and sarcastic political memes gain a large following and can sometimes neither be ignored nor responded to, since either course of action could easily backfire.

Those critical of meme culture point out that the medium is inherently susceptible to performative activism and that the use of humor depoliticizes issues. While these are legitimate concerns, the pros outweigh the cons. There is a long history of the use of political cartoons to poke fun at people in positions of power and explore controversial issues. But the ability to create and circulate these cultural products was confined to a few in the offline world. Internet memes are a phenomenon precisely because they open up this space for participation by millions of people, allowing them to cultivate a sense of solidarity based on political issues in a way that is ironic, humorous, and witty.

Conclusion

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, most of our everyday activities including resistance movements and activisms have moved online. Some of these changes will likely stay in the post-pandemic world. This is not to say that all forms of protests will, or should, move to the digital sphere, but tapping into the resources of memetic discourse offers us another avenue for dissent. When the #BlackLivesMatter protests picked up in late May and early June 2020, they had to inhabit offline spaces to ensure the sustainability of the movement and maximum impact. The interlinking of online and offline spaces and cultures is more pronounced now than ever before. So we need to use every arrow in our quiver to counter institutions with a lot more power and resources at their disposal.

Memes have become a part of contemporary resistance language; they are sites for battling ideological differences, quick and easy to produce and spread, and fairly robust against censorship due to their high mutability. Harnessing the power of these digital palimpsests can go a long way in enabling social activists to initiate greater and better political action.

The

The  A

A