The digital economy has brought major transformations that require new institutional arrangements. Tax systems are no exception. With the increase in cross-border economic activity and the rise of large technology companies, new challenges have arisen. The basic principles of international taxation, which were defined a century ago, are no longer fit for purpose. These rules need a thorough redesign. The negotiation of a Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (hereafter UN Tax Convention) is a once-in-a-century opportunity to change these rules in an inclusive and effective manner.

A Brief Historical Context

In 1928, the League of Nations presided over a debate between two tax approaches for multinational corporations. The unitary approach assesses multinationals’ total profits at the unit of the group, and then apportions that between the various countries of operation, in line with the share of economic activity in each. This method can be applied either by individual jurisdictions or globally.

In contrast, the League of Nations chose the separate accounting approach, where profits are assessed separately for each entity in a multinational, with the key rule being that transactions between entities should follow market prices, known as the “arm’s length principle.” This principle is criticized for being economically flawed, as multinationals, by nature, can make higher profits than a set of entities operating at arm’s length from each other, so that ‘true’ transfer prices for a multinational cannot be the same as arm’s length prices.

In 2013, the OECD, under the direction of the G20, was tasked with updating global tax regulations for multinationals. The Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) program initially seemed to challenge the existing rules. However, the BEPS Action Plan, approved later that year, largely upheld the status quo, with only minor adjustments to the rules.

In 2019, in recognition of the limits of this approach and under the auspices of a broader platform called the Inclusive Framework–made up of more than 100 jurisdictions but where the OECD secretariat ended up retaining real power–a second initiative known as BEPS 2.0 was launched. This agenda was kicked off through a consultation paper entitled ‘The Tax Challenges of the Digitalisation of the Economy’ whose initial ambitions also lost their reformist potential when proposals brought forward by the G24 in representation of developing nations were ignored in favor of an agreement negotiated bilaterally by the United States and France.

This outcome is what is known today as the OECD’s Two Pillar solution. Originally planned to deliver in 2020, neither of the two ‘pillars’ has been finalized—but both are visibly crumbling.

This outcome is what is known today as the OECD’s Two Pillar solution. Originally planned to deliver in 2020, neither of the two ‘pillars’ has been finalized—but both are visibly crumbling. The first pillar, intended to go beyond digital services taxes (DSTs) and render them superfluous, has become so restricted as to be nearly meaningless. Simple DSTs would increase revenue for most countries. The OECD’s second pillar is the global minimum tax. This, too, has lost much of its original ambition, and even global adoption would provide just a fraction of the money of proposed alternatives. Beyond the assessment of its potential benefits, the outcome of the US elections has perhaps been the final blow to an agreement that many had already written off as dead.

A More Inclusive and Effective Way Forward: the UN Tax Convention

In recognition of the ineffectiveness and lack of inclusiveness of an international tax order led by the OECD, the countries of the world–under the leadership of the African Group–have approved the terms of reference for the formal negotiations of a UN framework convention on international tax cooperation. Those negotiations will begin in 2025 and are scheduled to run until mid-2027.

As shown in the State of Tax Justice Report 2024, countries of the world are losing 492 billion a year to cross-border tax abuse. The UN Tax Convention has the potential to deliver comprehensive reforms to curb the problem of cross-border tax abuse that costs us all so much. The cost is counted not only in the huge revenue losses this report sets out for each country but in the major damage to the possibility of fiscally sound states that can guarantee rights such as health, education or finance the much-needed energy transition to protect people and the planet in the era of climate emergency and other interrelated crises.

This is the opportunity that the G77 and the tax justice movement have been pursuing for two decades, but one that can bring benefits to all nations.

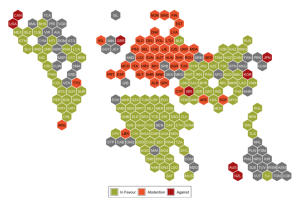

This is the opportunity that the G77 and the tax justice movement have been pursuing for two decades, but one that can bring benefits to all nations. As the map below shows, only 8 countries signaled opposition in the last vote in August.

Support of the UN Tax Convention -as per the vote at the Ad Hoc Committee to draft the Terms of Reference in August 2024. Source: Tax Justice Network

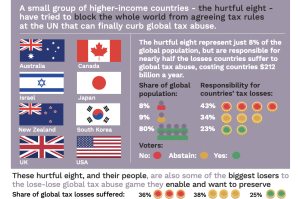

These countries, interestingly, are both big enablers of transnational tax abuses and big losers in terms of revenue losses. With only 8% of the world’s population, they are collectively responsible for 43 percent of global tax losses, but their population in turn suffers 36% of global revenue losses from transnational tax abuses.

Source: Tax Justice Network

These countries have the possibility to support the process for the benefit of their peoples at the next vote in December, when the General Assembly will decide on the terms of reference adopted by the Ad Hoc Committee in August and set the budget for next year’s negotiations.

What measures should the UN Tax Convention include to respond to the challenges of taxation in the digital age? The Tax Justice Network advocates for a Convention that incorporates the ABCDEFG of tax justice, meaning a comprehensive package of reforms to end corporate and high-net-worth individuals’ tax abuses, and generate a fair distribution of rights to tax cross-border economic activity between the Global North and the Global South (see image below).

Source: Tax Justice Network

The UN Tax Convention process is central to responding to key global challenges that have been discussed in other fora. With the G20 declaration adopted under Brazil’s presidency in 2024, in which member states commit to advance progressive taxation, including more effective taxation of high net worth individuals, the UN Tax Convention becomes the main vehicle available to deliver on these commitments with global transparency measures such as the creation of a Global Assets Register and an effective automatic exchange of information regime with differentiated responsibilities tailored to the capacities of different groups of countries.

The UN Tax Convention process is central to responding to key global challenges that have been discussed in other fora.

With pressing climate discussions around measures to close the financing gap, more effective tax cooperation to combat transnational tax abuses and strengthen the fiscal space of countries, particularly low-income countries, is an urgent need that the UN Tax Convention can facilitate.

Likewise, the UN Tax Convention can help mobilize the resources needed for states to finance the commitments made through the recently adopted Global Digital Compact, including those related to bridging the digital divide and expanding inclusion in the benefits of the digital economy for all. Finally, the UN Tax Convention can provide the regulatory framework for states to ensure that digital companies pay a fair contribution in taxes and that the benefits are fairly distributed across countries.