In October 2022, Google announced it will acquire a site in the south-western region of Belgium, its third in the area, after its 90-hectare hub in Saint-Ghislain (the first to be developed outside the US, 15 years ago), and its recently acquired 50-hectare site in the nearby city of Farciennes (where it plans to build a sixth data center in the country). The announcement was celebrated uncritically for the economic bonanza it was supposed to be for one of the poorest regions in Belgium. But this time around, it was also the environmental impact of the digital behemoth that made the news.

Indeed, both the Prime Minister of Belgium (Alexander De Croo, from the center-right party Open VLD) and the minister in charge of telecommunications (Petra de Sutter, from the green party Groen) made the trip. The latter made this telling comment: “There is no ecological transition without digital transition. But the reverse is also true. You can’t have a digital transition without an ecological transition. The weight of digital technology in energy consumption will increase in the coming years. We must therefore ensure that Google continues its efforts and sets an example for other players in ICTs.”

The “efforts” and “example” De Sutter is referring to is Google’s pledge to be “carbon-free” by 2030. And Belgium is a central piece of that plan. It is where the company has built its first solar farm counting more than 10,000 solar panels, and is currently testing “green batteries” to stock energy and replace diesel generators. As the Google director of energy and sustainability of data centers puts it: “We want every YouTube video viewed, every email sent, every song listened to on Spotify, at any time of the year to consume only renewable energy.”

Google and other Big Tech players are not only pledging to cut their carbon emissions to a minimum but are also assuming a central role in fostering the wider ecological transition. On its sustainability portal, Google explains that one of its missions is “to foster sustainability at scale by organizing information about our planet, and making it actionable through technology”. Similarly, Microsoft asserts, “No matter where you are in your sustainability journey, Microsoft cloud–based technology solutions can help you move forward.”

These arguments seem to have convinced most governments and international organizations. For example, in its strategy to “shape Europe’s digital future”, the EU Commission considers digital solutions to be “powerful enablers” for “sustainability transition” that “can advance the circular economy, support the decarbonization of all sectors, and reduce the environmental and social footprint of products placed on the EU market”. In a recent report, the UNDP has also contended that the “digital is an indispensable enabler for driving a green and inclusive recovery”.

And yet, current trends in digitalization worldwide present a contradictory picture. Take the tech industry’s own carbon footprint. Sure, there is a real push for energy efficiency and the use of renewables on part of the sector. But the exponential growth of the sector makes the former negligeable and the latter even more uncertain.

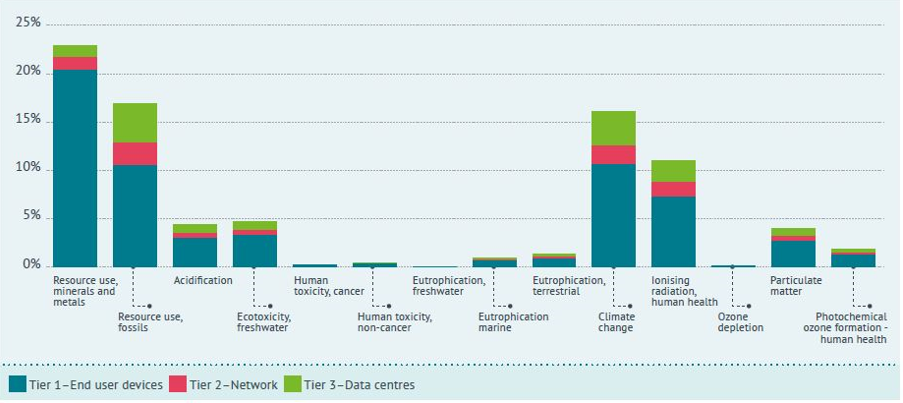

And the situation gets worse when you look at both the lifecycle of digital technologies, and their environmental impact beyond contributing to global warming. A recent study finds that the use of minerals and metals, and not climate change and fossil fuel use, is the most important indicator of the environmental impacts of ICT. The same study also finds end-user devices are by far the most impactful aspects of digital services, way ahead of networks and data centers, accounting for 54% to 90% of the total impact, depending on the indicators (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Weighted environmental impact distribution of digital services along the three tiers (end user devices, network, and data centers)

Source: Bordage et al. (2021: 32)

The result is that all the materials being displaced annually due to the production and consumption of digital services in the EU alone are about the same weight as all human beings on earth (9.2 billions human averaging 62 kg), while the amount of electricity being consumed by those services already represents 9.3% of European electricity consumption, and the amount of GHG they emit currently account for 4.2% of total European GHG emissions.

A recent study finds that the use of minerals and metals, and not climate change and fossil fuel use, is the most important indicator of the environmental impacts of ICT.

The trend is only worsening owing to the planned obsolescence and multiplication of connected devices, along with the hyper-concentrated and data hungry business model they are designed to feed. At the current pace, the digital industry could represent more than 5% of global energy consumption and contribute 8% to global GHG emissions by 2025, while over half of the more than 30 different elements that make up our smartphones “give cause for concern in the years to come because of increasing scarcity”.

Now, some would argue that this is, at least partly, counterbalanced by the positive impacts that digitalization brings to the sustainability of the economy at large. But this is highly questionable. The global diffusion of digital technologies in the last decades have not been accompanied by a decline in energy and resources consumption, quite the contrary. And the reason is simple: in a capitalist economy, technological innovations serve first and foremost, the maximization of growth and profit. After all, for all its talks about sustainability, Google is still mainly an advertising company, making money by selling ever more sophisticated tools to feed consumerism. And while data analysis and artificial intelligence (AI) are being celebrated for their (real) potential in the fight against global warming and towards environmental sustainability, right now the massive data collection and AI boom are mostly feeding unsustainable activities such as targeted advertising, high-frequency trading, bitcoin mining, or even oil and gas prospecting.

At the current pace, the digital industry could represent more than 5% of global energy consumption and contribute 8% to global GHG emissions by 2025.

These glaring gaps between the promise and reality of the ‘light’ ecological footprint of digital technologies should serve as warning against uncritically pleading for an unavoidable role of digital technologies in fostering sustainable development. Especially if we consider how deeply unequal the environmental record of digital technologies is at the global level. This is what Michel Kwet refers to as “the capitalist, imperialist, and environmental dimensions of digital power, which together are deepening global inequality and pushing the planet closer to collapse”.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for example, 70% of the world’s cobalt used in batteries is being produced in environmentally and socially catastrophic conditions, while the country has an internet penetration rate of only 17.6%, and there is an average 1.5 connected devices per person in Africa (against 9.4 in Europe and 13.4 in North America). Similarly, an overwhelming majority of today’s data centers are located in so-called developed economies mainly in North America and Europe, while their huge consequences on global warming and the wider environmental collapse will be felt most acutely in a digitally exploited or excluded Global South.

There is also the issue of digital waste. In 2019, 53.6 million tons of e-waste was generated worldwide, a number projected to grow to 74.7 million tons by 2030. Only a fraction of this is being recycled, and most of it ends up in garbage dumps in the Global South where it contaminates the air and soils, fueling large-scale sanitary crises.

So, what is to be done? The first thing is to acknowledge that you can’t have infinite digital growth in a finite world, to paraphrase a famous saying. This means we can’t keep pushing for the digitalization of everything and simply assume it will eventually align with ecological transition – it won’t. It also means we can’t keep advocating for a “digital catch up” from the Global South without questioning the levels and modes of digitalization in the Global North.

What we actually need is both global digital degrowth – to make sure that digital technologies are brought back into levels of production, use, and recycling compatible with planetary boundaries – as well as a complete reorganization of the digital economy that aims to distribute what we can actually afford in terms of digitalization in the most effective and socially just way, on a planetary scale. In order to do this, we must obviously oppose the mainstream digitalization agenda and all its latest greenwashing efforts. But we must also work in our own movements to better bridge environmental and digital justices issues, especially in a North-South perspective.

We can’t keep pushing for the digitalization of everything and simply assume it will eventually align with ecological transition – it won’t.

The good news is that there are a lot of, at least tacit, complementarities between the two spheres that can be built on. Users of free software and operating systems, for example, are generally able to make their devices last longer because they escape the planned obsolescence enforced by proprietary systems’ incessant updates. Limits imposed on the massive and systematic collection of personal data for privacy reasons can also help reduce the environmental footprint of the digital economy.

More fundamentally, the demands for a bottom-up, publicly, and democratically-controlled digitalization are a necessary (although not sufficient) first step towards any attempt at digital sustainability. And on the other way around, historical struggles to protect natural commons such as water or the climate could inspire much of the current reflections around the “digital commons”, while environmentally central concepts such as “food sovereignty” or “common but differentiated responsibilities” could also be fruitfully imported in the digital justice sphere.

This is not to say that it will be an easy conversation, but we should have it better sooner than later. Time is running out.