Contrary to the brick-and-mortar economies of decades past, the adoption of information technology today allows companies to reach consumers and users in many jurisdictions without a physical presence. For that reason, under a tax treaty, for example, countries lose a significant amount of revenue as highly profitable digital companies may not constitute a taxable presence, notwithstanding having significant economic involvement, in a jurisdiction. This is owing to the fundamental requirement under present international tax rules to have a physical presence in order to establish a taxable presence. Developing countries, most of which are net importers of services are disproportionately impacted by changing business models underpinned by technology.

This article discusses measures developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the United Nations (UN), and individual country measures for the taxation of the digital economy. These separate, uncoordinated measures may lead to uncertainty and increased compliance costs for businesses. In a highly digitalized global economy, many countries are pushing to find a global solution to address the challenges of taxing digital services under the United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation (UNFCITC) (hereinafter referred to as “framework convention”), with one of the expected early protocols being on the taxation of cross-border services. This article examines current approaches and suggests steps toward a coordinated global solution, outlining key components that should go into the protocol on taxation of cross-border services.

Current Approaches Developed for Taxation of Digital Services

The most notable efforts for taxing cross-border digital services are treaty-based measures which include Amount A under Pillar One of the OECD’s Two-Pillar Solution and Article 12B of the UN Model Tax Convention on the taxation of income from automated digital services (ADS). Amount A seeks to reallocate taxing rights to market jurisdictions by reallocating a proportion of the residual profits of highly profitable multinational enterprises (MNEs) to countries satisfying certain conditions.

Additionally, many countries have introduced national measures for taxing the digitalized economy, of which the most common is called a Digital Service Tax (DST). A few countries have also introduced another measure called Significant Economic Presence (SEP).

The urgency for a coordinated approach to the taxation of the digital economy has intensified with the delays and uncertainty in the implementation of Amount A, due to a lack of global consensus and unlikely adoption by key states, particularly the United States. The United States, which is home to most of the largest Big Tech companies, has in the past opposed DSTs and similar measures, perceiving them as discriminatory because they primarily impact U.S. multinationals, and has usually responded by threatening to impose retaliatory tariffs on the implementing countries. However, the US has also been perceived to be opposed to the Amount A solution. Republicans in the US Congress in fact voted to defund the OECD for trying to tax US corporations. There is a widespread perception that whether Democrat or Republican, the US will remain opposed to allowing other countries to tax its MNEs.

For this reason, many countries, both OECD and non-OECD, including the UK, France, Italy, Spain, India, Kenya, Tanzania, and Nepal, have already implemented different forms of DSTs in their domestic laws, and others are likely to follow with similar tax measures. These countries have already collected millions from DSTs, showing them to be a proven revenue generator. The European Union Council has made indications of introducing a digital levy in the event that Amount A fails.

Nevertheless, a plethora of uncoordinated and varying national measures can lead to increased compliance burden for businesses, double taxation, and disputes between countries and taxpayers.

Nevertheless, a plethora of uncoordinated and varying national measures can lead to an increased compliance burden for businesses, double taxation, and disputes between countries and taxpayers. Keeping in mind the highly likely failure of the OECD solution of Amount A, the terms of reference for the framework convention indicates that one of the early protocols will address the taxation of income derived from the provision of cross-border services, in an increasingly digitalized and globalized economy, expected to be concluded by 2027. In effect, this will be the UN’s multilateral solution for taxing the digital economy.

Given that most countries that have initiated national measures have used DSTs, it is likely that the UN’s solution will build on them. The Secretary of the UN Tax Committee said “they are here to stay” and suggested a “common approach” to DSTs as the way forward. For this reason, it is important to briefly examine their impact, especially when contrasted with the OECD solution of Amount A.

Digital Service Taxes vs Amount A

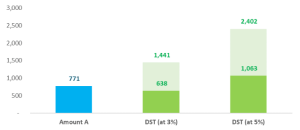

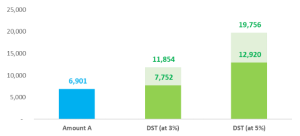

DSTs target highly digitalized activities like online advertising, platform intermediation, social media subscriptions, search engines, cloud storage, etc, that derive incomes from market jurisdictions while paying no taxes on such incomes due to the nature of the activities. Some of the benefits of DSTs include: DSTs allow the market jurisdictions to tax the income earned by digital businesses within their borders, even without a physical presence; they are relatively simple to administer; they are considered efficient as they target companies that are often near-monopolies, whose behavior is unlikely to change significantly in response to the tax; DSTs generate additional revenue for the taxing jurisdiction without increasing the taxes for local residents. Revenue estimates by the South Centre, in collaboration with the West African Tax Administration Forum and the African Tax Administration Forum, show that the 85 combined Member States of the African Union and the South Centre can expect between EUR 20-34 billion from a 5% DST compared to EUR 7-10 billion in revenues from Amount A.

Figure 1: 2022 Tax Revenue Estimation under Amount A vs. DST Regimes for African Union Members (EUR Millions) Source: South Centre, West African Tax Administration Forum et al (2024)

Figure 2: 2022 Tax Revenue Estimation under Amount A vs. DST Regimes for South Centre Members Source: South Centre, West African Tax Administration Forum et al (2024)

Estimates by the EU Tax Observatory show that far from giving developing countries additional revenues, Amount A may actually lead to an erosion of taxing rights for some countries. For example, a country like India stands to lose EUR 89 million from Amount A, instead of gaining anything. Vietnam, Swaziland, Jamaica, and several other countries face similar consequences.

Estimates by the EU Tax Observatory show that far from giving developing countries additional revenues, Amount A may actually lead to an erosion of taxing rights for some countries.

While it is clear that developing countries can benefit up to more than three times on average from DSTs compared to Amount A, DSTs are not without criticisms. Critics argue that they discourage innovation and affect productivity, are discriminatory, may lead to multiple or double taxation, and are usually shifted to the consumers. These criticisms are often speculative without substantial data to back them up.

In any case, shifting DSTs to consumers may not always be feasible due to the risk of reduced demand and competitive disadvantages. For example, a report by the Computer & Communications Industry Association showed that if US companies passed on the UK DST to UK consumers, it would harm the US companies by $4.4 billion per year and lead to the potential loss of 5,914 jobs in the US. Thus, passing on the tax to consumers can cause real damage to the economies of developed countries, and for that reason is, to some extent, an empty threat. This is something developing countries should be aware of.

Nonetheless, as mentioned previously, a standardized and harmonized approach to DSTs can ease the political tension between developed and developing countries, provide a viable multilateral solution, and also reduce compliance costs for businesses. The following outlines what such an approach could look like.

Components of the Framework Convention Protocol on Cross-Border Services

Scope: critical importance of including Automated Digital Services

The first and most important requirement is to ensure that the protocol includes Automated Digital Services (ADS) in its scope. The bulk of the revenues derived from Big Tech MNEs like Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Meta (Facebook), etc comes from ADS, such as online advertising, platform intermediation, search engines, social media, and other services requiring minimal human involvement from the service provider. These are the key services targeted by DSTs and must be covered by the first early protocol.

The bulk of the revenues derived from Big Tech MNEs like Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Meta (Facebook), etc comes from ADS, such as online advertising, platform intermediation, search engines, social media, and other services requiring minimal human involvement from the service provider.

This will most likely be opposed by developed countries who will argue that it should be covered under the topic “taxation of the digitalized economy”, which is one of the topics for consideration as the second early protocol. They will then try to ensure that another topic is chosen, for example, taxation of High-Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) or prevention of tax disputes.

This way, in effect the taxation of Big Tech multinationals will be removed from the scope of the framework convention, leaving Amount A as the only multilateral solution on the table. The developed countries will then push for its early ratification and implementation.

Further, developed countries will likely try to restrict the scope of the protocol to other kinds of service provision like design, software development, etc, which will increase the tax burden on small firms while letting the Big Tech multinationals off the hook.

This must be prevented, and developing countries must insist that the scope of the protocol includes Automated Digital Services. This should be a non-negotiable if the framework convention is to provide a viable alternative to the OECD’s solution.

Paragraph 6 of Article 12B of the UN Model Tax Convention provides a definition of “automated digital services” and can be a good starting point for the negotiations. There can also be an option to use revenue threshold to reduce administration costs and focus on the big companies. Alongside a comprehensive definition of cross-border services, the next section offers some suggestions for other key components that could form part of the protocol.

Other components

The remainder of the protocol can include a common understanding of:

Applicable rates: The protocol can prescribe an acceptable range of rates for DST to prevent too high or too low rates. The Commentary on Article 12B suggests 3-4% which can be a good starting point for the negotiations. This rate can vary depending on the nature of digital services and their level of profitability.

Taxable presence: The protocol can also provide a mechanism for modifying the permanent establishment and business profits provisions in existing bilateral tax treaties to incorporate the principle of Significant Economic Presence (SEP), to create taxable presence for digitalized multinationals in the countries where they derive revenues. SEP can be implemented using a simplified approach such as based on a percentage of revenues generated, number of users, data collected in the source state, or any other metric depending on the nature of service or digital activity. Paragraph 3 of Article 12B which addresses the net basis method for taxing the digital economy can also be considered in the negotiations, with further simplifications.

Elimination of double taxation: Countries can establish mechanisms to eliminate double taxation. There can be a commitment by countries that if a company has paid a DST that meets the common understanding, then the taxpayer will be granted relief by exemption or credit method. For example, if a Big Tech firm is headquartered in a developed country and pays a DST to a developing country and the DST meets the conditions prescribed in the protocol, then the developed country can provide tax relief to eliminate double taxation. If a country chooses not to participate, its companies will suffer double taxation and could become less competitive. This approach can therefore incentivize the participation of all countries in the protocol.

The taxes paid by MNEs, whether DST or SEP tax, are based on a proxy of profits and directly affect the shareholders’ after-tax returns, hence they should be creditable against other tax liabilities in their residence country. This ensures that digital businesses contribute fairly to the economies where they derive their revenues without suffering double or multiple taxation.

Standardized returns: Countries should develop standardized returns and filing requirements for MNEs. This will reduce the administrative burden for multinationals and tax administrations and increase certainty.

Mutual assistance in enforcement and recovery of taxes: Mutual assistance in the enforcement and recovery of taxes to enhance administration efficiency, particularly benefiting low-income countries with limited capacity to enforce tax obligations on MNEs headquartered in other jurisdictions.

Dispute resolution: Dispute prevention and resolution mechanism for any disputes arising.

Convention or Political Commitment?

A critical question is how the above will be implemented. Two options can be considered.

Multilateral Convention: This would be an Amount A-style convention that would have to be signed and ratified by countries and be legally binding. This option is more stringent and may discourage developed countries from joining, especially given the commitment to provide tax relief, which in effect is an acceptance of giving up their taxing rights.

Political Commitment: This would be a Pillar Two-style non-binding “common approach” which is primarily a political commitment. The protocol would primarily provide a legal framework where countries can regularly discuss relevant issues like scope, applicable rates, dispute resolution, etc. This option is less stringent and can incentivize more developed countries to participate, albeit with reduced tax certainty for businesses.

Conclusion

This article has examined measures developed for the taxation of the digital economy, including OECD’s Amount A of Pillar One, Article 12B of the UN Model Tax Convention, and unilateral measures like the DSTs. It has discussed the hurdles delaying the implementation of Amount A and the subsequent response by many countries who have implemented various forms of DSTs. DSTs allow countries to tax the income earned by digital businesses within their borders, even without a physical presence, and are relatively easy to administer. However, the uncoordinated unilateral DSTs are likely to increase compliance costs and tax disputes. Thus, a unified global approach is urgently needed to streamline compliance. The article has suggested key components for inclusion in the expected UNFCITC’s first protocol on the taxation of cross-border services, such as a comprehensive definition of cross-border services, and key considerations for countries as they work towards a unified approach.