By 2022, it is estimated that the annual global internet traffic will reach 4.8 zettabytes or 4,800,000,000,000 GB. That is the equivalent of 150,000 full-length movies flowing through the internet in a single second – a 1,000 percent increase in web traffic from just 20 years ago.

This rise is driven not only by a larger number of people using the internet, but also by the significant increase in per user consumption of the internet. With the Covid-19 pandemic pushing internet use across the world, lockdown measures drove international internet capacity from 450 terabytes per second (TBps) to 600 TBps; a 35% increase between 2019 and 2020. Median monthly usage for the end of 2020 was 293.8 GB, a 54% increase compared to the end of 2019, when it was 190.7 GB.

Big Tech firms have benefited greatly from the increased reliance on the internet, reflected in the massive jumps in their profits during the pandemic. This growth is unsurprising since research indicates that even before the pandemic, nearly 50 percent of the internet’s global traffic was being shared by only six firms (Google, Netflix, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, and Amazon). Having established themselves as the go-to interfaces for online communication, media, and e-commerce, particularly in developing countries, these companies are more invested than ever in ensuring the growth of the internet and claiming the ‘next billion users’.

The last few years have brought greater scrutiny of Big Tech business practices. Internet regulators have so far concerned themselves primarily with the web platforms these firms represent, focusing on anti-competitive practices facilitated by business models built on surveillance capitalism and data governance blind-spots. Emerging regulations in the EU and China, particularly, have aimed to direct the use of data and algorithms to promote more competitive online market environments. The scope and efficacy of these measures have been found wanting on many counts, and the debate on how to rein in Big Tech continues to rage on.

However, when it comes to fully confronting the problem of corporate capture, these proposed regulations may only be one piece of the puzzle. We need to also probe the foundation on which the internet operates – the vast, physical networks of cables, servers, and other hardware that constitute cyberspace – and who increasingly controls it.

How Does the Internet Work?

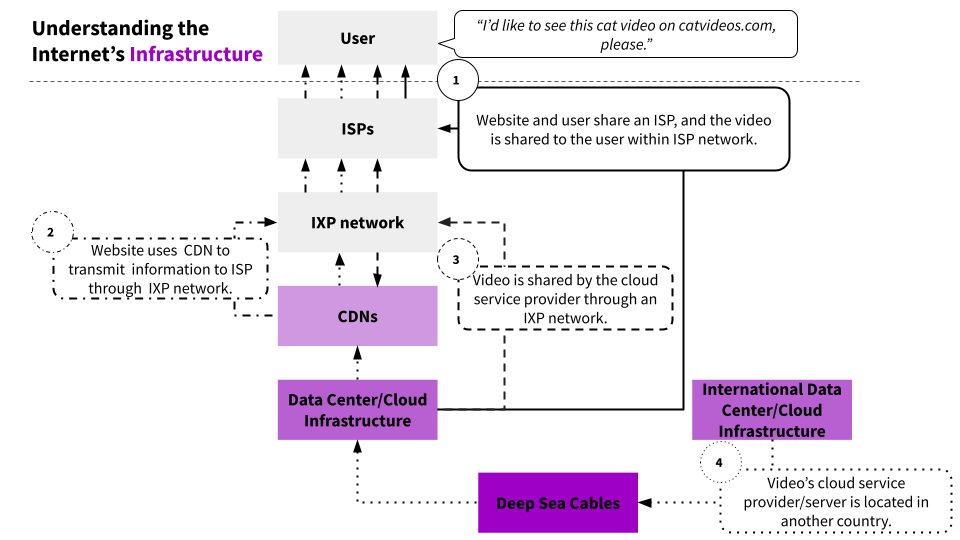

Let us do a simple exercise to trace the internet’s infrastructure through an example. Let us say, you request a cat video from an Internet Service Provider (ISP) – the broadband company that connects to your home. There are, by and large, four routes available for the internet to provide that video to you, each of which is attempted sequentially until success, as discussed below:

1. If you are lucky and catvideos.com happens to be operated by someone who lives close by, it is possible that you may share an ISP with the website, and the video can then be requested and delivered within a single ISP network. However, the chances of this happening are low, and depend on your using a specific internet vendor.

2. If this is unsuccessful, the ISP will check with co-located Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), which maintain copies of popular content to be able to serve users quickly, on demand. If the website has paid a CDN to host its information, the ISP will route the information from the CDN to you through a nearby Internet Exchange Point (IXP) that your ISP is connected to. Over the years, this has become the most prominent method of content access and transmission, with CDNs emerging as an important tool for platforms and websites looking to increase the quality of their services.

3. If the video has only recently been put online by the website and is still unavailable with CDNs, the IXP will attempt to communicate with other IXPs to find the shortest route between you and the servers being paid for by the website you requested content from, typically hosted by cloud computing services providers, especially in the case of smaller websites and applications, like catvideos.com. If the website is being hosted in your country, the ISP will route the video from the data center to you. It will also likely store a copy in the CDN for future use (if paid for).

4. If the website is not hosted in your country, the video will move through a vast network of deep-sea cables connecting large IXPs around the world. The cables will route the information from international data centers hosted by public cloud providers through a network of IXPs to you through your ISP. The bandwidth or capacity of the cables connecting to your IXP are a major deciding factor in how fast the video reaches you.

The graphic represents possible routes taken by content through the internet when a user requests to see a cat video. CDNs, cloud facilities, and underwater deep sea cables are highlighted as vital parts of the content delivery infrastructure.

Trends in Infrastructure Ownership and their Implications

So what do these various probabilities to access catvideo.com tell us?

Big Tech firms have increasingly been expanding their ownership of the bottom three layers of the internet’s physical infrastructure. While ISPs have largely remained extremely localized services offered by domestic telecommunications companies and broadband service providers, IXPs have benefited from shared ownership by states, run largely as not-for-profit exchanges of information between various ISP networks.

Content Distribution Networks (CDNs)

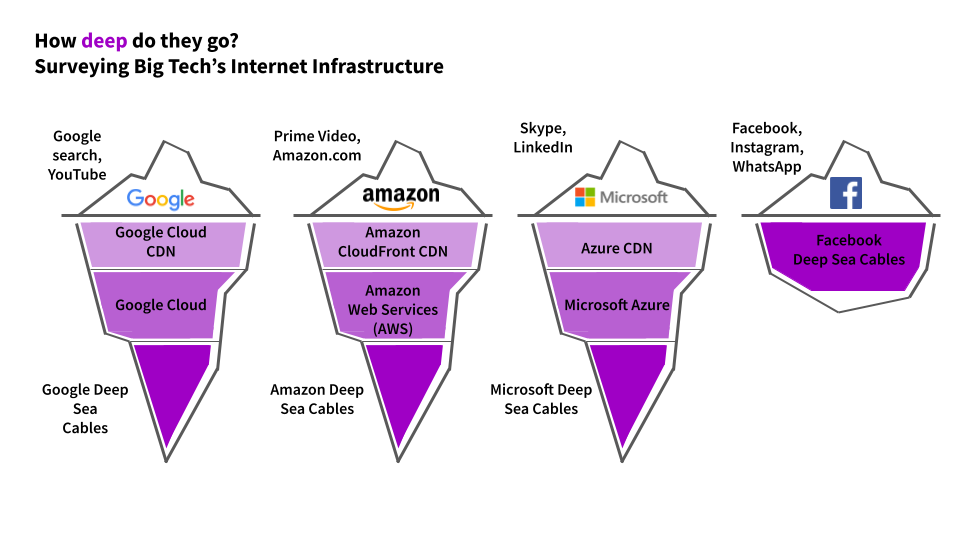

Beneath their digital platforms, Big Tech companies offer services across the infrastructure for content delivery on the internet. The graphic represents the different services they offer, either directly (CDN or cloud) or indirectly (cables). Facebook CDN and cloud facilities are omitted since they are used internal to Facebook only.

The use of CDNs has grown sharply over the last 10 years, driven by the exponential rise in the share of video content during the period. Cisco’s 2016 forecast projected that 78% of all internet video traffic will flow through CDNs in 2021, up from 67% in 2016.

In the late 2000s, CDNs emerged as a way for Big Tech to tackle the challenges of poor internet speed while buffering video content. While pure-play CDNs were the norm up until this point, a majority of the Big Tech firms that disseminate video content have since set up their own networks for both internal use and sale to other websites or platforms. This has benefited users through seamless access to on-demand content.

However, when it comes to fully confronting the problem of corporate capture, these proposed regulations may only be one piece of the puzzle. We need to also probe the foundation on which the internet operates – the vast, physical networks of cables, servers, and other hardware that constitute cyberspace – and who increasingly controls it.

However, in the long term, the internet could suffer if small content providers are unable to survive independently, stifling creativity, and reducing the variety of content that exists outside of large Big Tech platforms. To be able to compete with YouTube’s video delivery speed, for example, catvideos.com will either have to hire a CDN to host their content across the globe, or simply become part of one of the bigger platforms.

The user’s right to access content and the producer’s right to participate in the internet economy are thus contingent on private infrastructures of internet connectivity.

Cloud Services Providers

The dominance of Big Tech in internet ownership is more visible, and arguably has more ramifications when considering cloud infrastructure. Four companies today own 67% of the world’s $130 billion cloud market (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Alibaba). Unlike CDNs, which witnessed a gradual increase in participation of Big Tech over the last decade, the advent of the cloud computing industry may be traced back to Big Tech, starting with Amazon Web Services (AWS) in 2006.

As an alternative to hosting independent servers, employing cloud service providers gives platforms and websites the ability to scale dynamically to respond to user demand. However, the downside is that cloud providers act as gatekeepers for the platform and its content. This means that cloud providers of catvideos.com could choose to remove it from the internet. The vital question about ‘de-platforming platforms’ has become prominent in light of AWS pulling Parler off the internet in 2021, together with cases such as CloudFlare and Daily Stormer.

Apart from content distribution, cloud computing has also become an integral part of data analytics and Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems, with the prowess for storage and processing of large data sets. The monopolization of cloud services by Big Tech thus represents control not only over the content that newer platforms host, but their AI ambitions as well. Through cloud infrastructure for AI, Big Tech companies have steadily integrated themselves into state functioning as well, drawing criticism based on concerns about data security and AI ‘cold wars’.

Underwater Deep-Sea Cables

Sitting beneath all these parts of the internet is a vast, global network of underwater sea cables connecting cloud data centers and IXPs. Despite the increasing adoption of CDNs (cables aren’t required if the content is available with a CDN), demand for bandwidth from these cables reached an all-time high during the pandemic.

Historically, these cables have been owned by consortiums of telecom providers. However, since 2010, Big Tech firms have been investing in these cables as co-owners. Google went one step further in 2019 with Curie, financing an entire cable on their own – making it one of the first major non-telecom companies to build a private intercontinental cable. Since the completion of the Curie project, approximately 20% of the entire length of underwater sea cables in the world have been owned or co-owned by Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft. This figure is on the rise, with Facebook’s announcement of ‘2Africa’ in 2021, which is set to be the longest underwater sea cable in the world, spanning more than 37,000 km, circumnavigating Africa with connections to the Arabian Gulf, India, and Pakistan. According to Alan Mauldin, the Research Director of Telegeography, this trend will likely continue with Big Tech investments accounting for 30-50% of the overall total investments in undersea cables by 2023, to ‘link their largest data centers in Europe and Asia back to the US’.

If the core infrastructure underpinning the internet economy is co-opted by Big Tech, it would amount to an absolute dependence on the latter and greatly limit the scope and success of new initiatives. As more sectors of the economy and institutions of governance start relying on digital technologies to perform their functions, this dependence is only likely to increase.

The implications of this trend may not be immediately clear. While consumers will likely benefit from increased internet access at lower prices, smaller companies may be at a disadvantage if charged higher prices for bandwidth in the future. Privacy concerns have also been raised, if, say, Facebook was to use all data passing through their cable to ‘improve their services’, regardless of who owns the data.

Policy Implications

Put together, these trends represent a significant shift towards a privatized internet infrastructure, with researchers highlighting that tech giants are “gaining control over not only the content but the means of transferring the content”.

Encompassing concerns of neutrality in content transmission, the potential for anti-competitive practices, and data privacy, the implications of Big Tech’s control of the internet’s physical infrastructure closely resemble the implications of platforms and applications, and older debates of network neutrality. While platforms and applications have received or started receiving attention from regulators, the infrastructure on which they are built is yet to achieve the same level of recognition.

If the core infrastructure underpinning the internet economy is co-opted by Big Tech, it would amount to an absolute dependence on the latter and greatly limit the scope and success of new initiatives. As more sectors of the economy and institutions of governance start relying on digital technologies to perform their functions, this dependence is only likely to increase.

Much has been written about the potential of the internet in spurring community-led innovation and knowledge sharing since its inception. To protect these features, it is necessary for states to come together to decide whether the internet should be governed as a global public good; and consider managing its infrastructure as a commons. As Brett Frischmann puts it, “Ultimately, the outcome of this debate may very well determine whether the internet continues to operate as a mixed infrastructure that supports widespread user production of commercial, public, and social goods, or whether it evolves into a commercial infrastructure optimized for the production and delivery of commercial outputs.”