In 2017, Toronto, Canada announced an ambitious plan to build a city ‘from the internet up’. The plan envisaged a city built with sensors and ubiquitous computers, constantly tapping into residents’ movements, habits, and locations to generate data that could ostensibly be used for empowering the same citizens and improving urban governance. From the very beginning, the project, contracted out to Google Inc. subsidiary Sidewalk Labs, was embroiled in controversy about the way urban space would be reconfigured to enable near-constant surveillance, and the opaque and non-participatory manner in which citizens’ data would be gathered, controlled, and used. By 2020, the vision of the Toronto Smart City had fallen to pieces, and the project was canceled after sustained efforts by activists and residents.

The parable of Sidewalk Toronto is increasingly relevant for cities around the world aspiring to tap into advances in information technologies and data analytics in an effort to recreate themselves as ‘smart cities’. Governments are increasingly keen on leveraging data as a resource to facilitate processes of urban governance and economic production; for instance, making decisions about how to manage public utilities like roads, electricity, and water, or using information about residents and urban communities to inform law enforcement, healthcare, and other crucial public services. This entails imbuing urban infrastructure with greater data collection capabilities, and employing Big Data analytics with the intention of facilitating urban governance and innovation. In practice, however, using these data-based technologies for urban governance often involves handing over the data and governance of urban environments to private contractors, increased surveillance of urban spaces, and alienating residents from control of and participation in civic spaces and urban governance. How might India’s smart cities avoid these pitfalls by learning from the failure of data governance in Sidewalk Toronto?

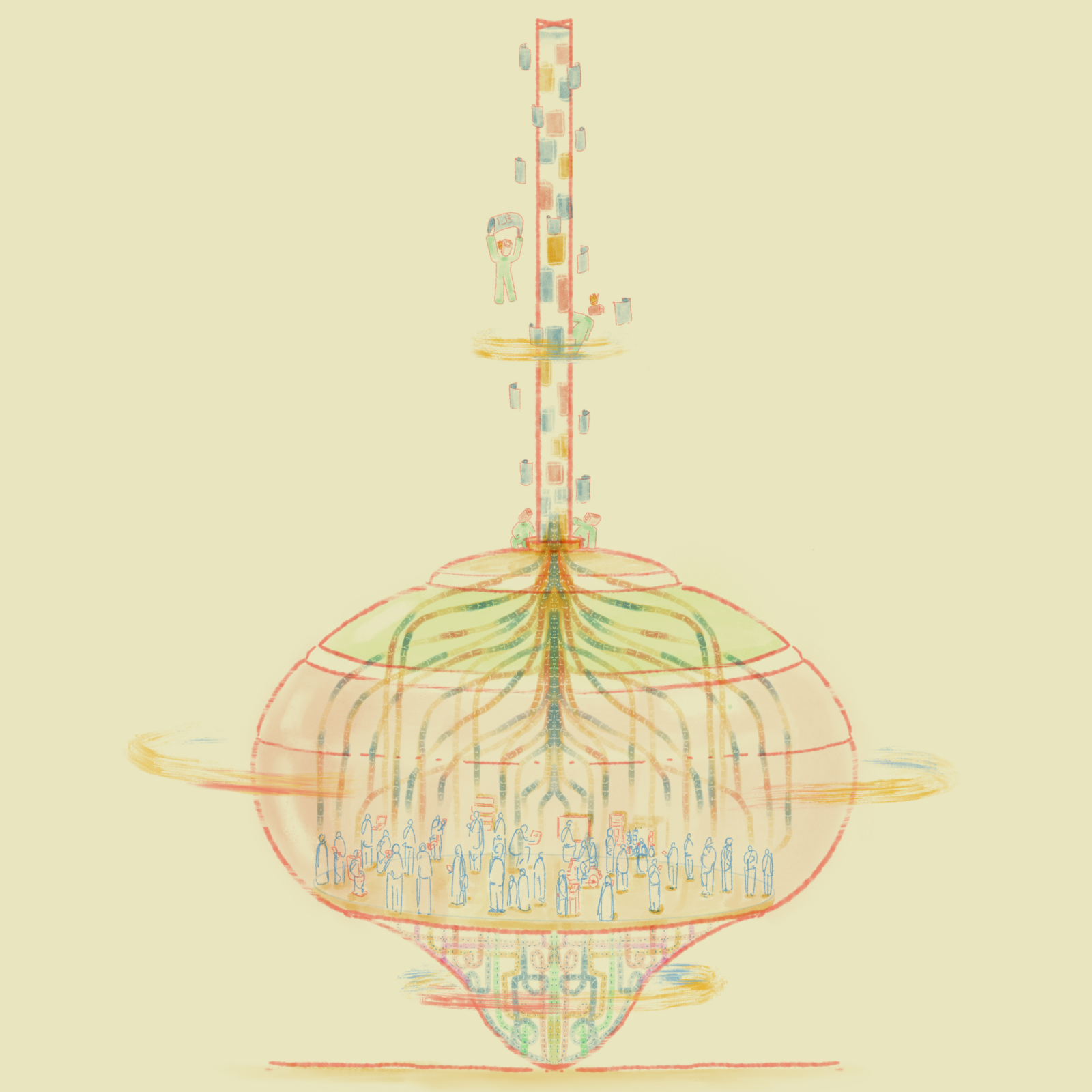

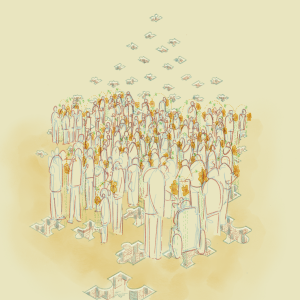

Hierarchical data flows in the Smart City, with the ‘bending’ of norms by governments and corporations providing momentum to the ‘top down’ governance of citizens’ data. Illustration by Paulanthony George.

Hierarchical data flows in the Smart City, with the ‘bending’ of norms by governments and corporations providing momentum to the ‘top down’ governance of citizens’ data. Illustration by Paulanthony George.

Data Governance in India’s Smart Cities

“Earlier, we made decisions without any base — education or health. The future will be digital governance and data.” — Nagpur City Data Officer

The Government of India’s intentions of utilizing data and digital technologies in urban governance are apparent from a plethora of initiatives undertaken primarily under the umbrella of the Smart Cities Mission – a 100 billion USD project for techno-centric urban rejuvenation. Utilizing data generated about cities and their residents – through the digitization of urban infrastructure using sensors, smartphones, and satellites – plays a major role in the vision of smart cities. This has also given rise to institutional and policy arrangements for how the data thus generated should be governed. Increasingly, India’s smart city vision is beginning to echo the sentiments that Sidewalk Toronto was criticized for – centralized decision-making processes to drive data collection and analysis, and collaborations with, or outsourcing to private actors.

The National Urban Innovation Stack, for instance, intends to form a set of protocols and technologies as information infrastructure for use by private and public entities. This ‘core data infrastructure’ will integrate all manner of existing government databases as well as more granular information which is being collected from censored environments, through mechanisms like the Urban Data Exchange. Essentially, the Urban Data Exchange is meant to create a ‘marketplace’ for urban data in order to enable innovation by private agencies ostensibly providing civic services, such as grievance redressal, identity verification and authentication, payments and billing, or geospatial mapping.

Other smart city programs, such as the DataSmart City Strategy and the related model frameworks for City Data Policies, echo similar data governance visions. These too envisage highly centralized information systems, like the Integrated Command and Control Centers for city surveillance. The data being generated is treated as the ‘property’ of specific departments or offices, and executive officials are responsible for implementing and overseeing governance mandates, including what data should be made available, to whom, and how.

Using these data-based technologies for urban governance often involves handing over the data and governance of urban environments to private contractors, increased surveillance of urban spaces, and alienating residents from control of and participation in civic spaces and urban governance.

The vision of urban data governance outlined in these documents is one that either places control of urban data in the hands of a centralized executive, or outsources these decisions to market-based actors. Neither of these consider how urban communities about whom data is being generated might have a say in aspects of data governance – how and what information about them is generated, the extent to which it should be shared or commoditized, and what values data governance might seek to promote. The ‘marketplace’ model of the Smart City – where commercial interests are prioritized and important public policy choices about data and governance are outsourced to private actors – is precisely why Sidewalk Labs was so strongly opposed. Despite its claims to create a ‘data trust’ for safely collecting and processing citizens’ data, it was the lack of civil participation and democratic deliberation throughout the process of ‘datafying’ the city which ultimately led to a failure of trust between the proponents of the project and the residents of the city.

As urban governance increasingly relies upon data and data-based technologies, it necessarily entails claims about the ‘ground reality’ which is being indicated by data, and this ground truth is far from objective, rather, it is as politically determined and contested as any other consideration that shapes public policy. For example, the visibility created by ‘open’ data, such as geospatial mapping efforts, can make the lives of people in informal settlements more precarious, potentially exposing them to eviction and empowering politically powerful actors to use this information against them. In other cases, the datafication of urban infrastructure like roads, electricity, or water utilities can prevent meaningful democratic participation about important questions of policy, which become subsumed within opaque and often privatized data processing projects which make decisions about how public resources should be allocated and managed.

The datafication of urban infrastructure like roads, electricity, or water utilities can prevent meaningful democratic participation about important questions of policy, which become subsumed within opaque and often privatized data processing projects which make decisions about how public resources should be allocated and managed.

These claims cannot be resolved only with reference to individual privacy, or by demarcating information as ‘open’ (public domain) or closed (government-controlled) datasets. Rather, they require more holistic considerations of how data might be governed as a shared resource between different stakeholders – encompassing individual privacy-related interests and democratic claims to open data and the public domain, but also socio-cultural and economic interests of particular communities to whom data relates. This might, for example, include legal claims to intellectual property, or culturally significant data that is being expropriated from communities without their consent.

Ultimately, these examples indicate the need to center meaningful participatory decision-making in urban data governance, including acknowledging the agency of the various communities of people whom the data pertains to or who are affected by these datafication efforts. It also requires going beyond binaries of closed/open and public/private data, towards engaging urban communities in data governance to reflect upon questions of what data gets collected and through what standards, how conflicting rights and interests might be negotiated and resolved, and how individual members of communities might exercise agency over data about the community.

Data Commons for India’s Smart Cities

The principles of commons-based governance – which emphasize sustainable management of shared resources without assigning private property rights or relying on centralized management by governments – present some possibilities for governing data as a community resource, or, in other words, building a ‘data commons’.

Cities like Barcelona and Amsterdam have explicitly attempted to take a commons-based approach to data governance, both by creating digital public infrastructure, and ensuring that the organizational, institutional, and legal mechanisms underpinning the governance of these infrastructures and data are transparent and open to public scrutiny and community management and participation. These approaches are a response to the current model of data ownership and use, where service providers unilaterally appropriate and govern value created by data from people. The objective is to enable stakeholders like researchers, emergency services, etc. to access urban data, while allowing citizens to set granular and dynamic rules for when their data may be shared.

Commons-based approaches to urban data governance can center the community’s participation beyond the dichotomy between centralized, government-managed, closed datasets, or private enclosure and appropriation of urban data. These approaches emphasize governance elements such as the presence of accessible dispute resolution mechanisms, systems of accountability and monitoring, frameworks for proportionate sanctions, etc. These mechanisms allow institutional processes that can be responsive to the needs and interests of a diverse set of stakeholders and enable-bottom-up governance matched with local contexts. The defining principle is participation from the community in determining rules related to access, use, and governance of resource systems.

The process of digitization and prioritization of data analytics should not come at the cost of transparency and democratic participation in how communities choose to be known and governed.

Commons-based data governance has important precursors in digital and pre-digital forms of information management that are already being practiced by communities, including in the Global South. Consider, for example, the practices of establishing policy and standards for the collection and sharing of statistical data by indigenous groups around the world, or the governance of traditional knowledge resources by communities which attempt to interface community management with standards and laws governing intellectual property.

Supporting urban governance processes with better data and information about the city is an important requirement. However, the process of digitization and prioritization of data analytics should not come at the cost of transparency and democratic participation in how communities choose to be known and governed. India’s ‘smart cities’ have a unique opportunity to learn from the experience of failed projects like Sidewalk Toronto towards building technological infrastructure and governance processes that are equitable and participatory.

Illustrations by Paulanthony George.