The precarity faced by workers on digital platforms precedes the Covid-19 pandemic. However, as with other low-wage insecure workers, the pandemic has exacerbated existing vulnerabilities experienced by platform delivery workers as companies prioritize market share over workers’ rights. In the absence of meaningful relief measures from platforms and governments, workers are falling through institutional cracks. It is, therefore, more urgent than ever, to push for regulatory measures to ensure workers’ welfare.

Platformization of Services and Governance

By now, it has been widely noted that platforms have reacted to the crisis with great speed to protect, and in some cases even consolidate and expand, their market share. Taking advantage of an asset-light business model—on-demand platforms do not own a majority of the infrastructure they are dependent on for business—platforms have been able to scale and expand with ease, and are left with enough capital in hand.

This advantage has allowed them to quickly pivot their services during the pandemic. A few days into the lockdown in India, ride-hailing platform Ola offered 500 vehicles to be used to deliver food and essentials in partnership with the Karnataka state government. In India’s national capital Delhi, Uber pledged INR 75 lakh in free rides so that the government could provide transport for healthcare workers. It also partnered with Flipkart and BigBasket for last mile delivery of essential items during the lockdown. UberEats resumed services to deliver essential items in Bangladesh , South Africa , and Sri Lanka. At one point, Amazon USA was considering home delivery of Covid-19 testing kits in collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Elsewhere, Airbnb and Oyo Rooms offered free stay for health workers.

Besides the asset-light model, platforms were also quick to take advantage of an on-demand workforce for task-based jobs that need little training or re-skilling. This workforce is also hyper-flexible, allowing platforms to switch between services relatively easily.

Platforms are also able to keep operating expenses low, shifting costs to workers and customers.

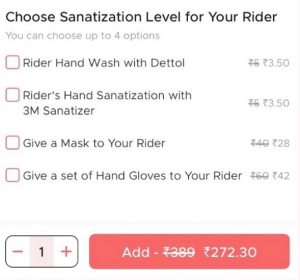

Finally, platforms are also able to keep operating expenses low, shifting costs to workers and customers. Even before the lockdown, these services were able to shift much of the operating cost on to workers, who had to pay for fuel, auto insurance, and maintenance themselves. Some workers even had to bear the costs of platform-mandated uniforms or branded equipment. The shifting of responsibility continued during the pandemic as platforms failed to provide additional equipment to help workers. As food delivery services shifted to grocery deliveries, workers had to factor in more time to go into stores to select goods that customers ordered. However, this extra time was not accounted for in the incentive structure. It’s not just workers who bear the burden of additional costs. Zomato customers, while placing their order, can now choose the level of protection their delivery workers should have, starting with hand soap, to sanitizers, to masks and gloves. The costs are added to the customers’ final bill but it remains unclear whether workers get even a fraction of the money that is collected from customers to cover the cost of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Relief Measures for Workers

For gig workers who work in close contact with people, PPE, including face masks, hand sanitizers, and gloves, is a necessity. However, till date, workers complain of having to purchase their own protective equipment. In the early days of lockdown, food delivery platform Swiggy asked workers to purchase their own PPE, promising that they would be reimbursed later. However, worker unions told Tandem Research that the reimbursement process was so cumbersome that it became almost impossible to claim expenses. As a result, the cost of PPE often fell on workers themselves, over and above the usual costs related to vehicles, such as petrol, loans, and taxes. This at a time when their incomes were already badly affected due to the ongoing crisis.

In many cases, the cost of PPE fell on the worker themselves, over and above the usual costs related to vehicles, such as petrol, loans, and taxes. This at a time when their incomes were already badly affected due to the ongoing crisis.

Health insurance is vital for all on-demand gig workers, not just during a period of crisis, but also during normal times. However, most platforms had failed to do this. Some added it to their relief measures during the pandemic. In India, Zomato announced a health insurance plan for workers who continued to work during the lockdown—workers would be eligible for consultations through telemedicine services, coverage of up to INR 5,000 for OPD (outpatient department) costs, Covid-related hospitalisation charges of up to INR 1 lakh, and compensation of INR 500/per day. Ola also partnered with a telehealth firm to offer workers outpatient consultations and insurance in case of Covid-related illnesses.

Several platforms started fundraising drives to raise money to support workers with emergency support, medical expenses, and essential groceries. Some requested donations from the public for these emergency funds, such as Ola Cabs’ ‘Drive the Driver’ fund and Zomato’s ‘Rider Relief Fund’ but provided little transparency on how these funds were being utilized or the eligibility criteria for workers to be able to access these funds. Some Uber drivers had received one-off transfers of INR 3,000 from Uber to cover their loss of income due to the pandemic, but there was little evidence that all drivers received this or of follow-up payments.

Some platforms stated that they would provide income and medical support to workers if they contracted the virus. Ola and Swiggy assured workers that they would cover any loss of income for drivers and their spouses if they were diagnosed with Covid-19 through INR 1,000 per day payments for up to 14 days. However, the support was contingent on a positive Covid-19 test, which remains largely inaccessible and highly expensive for the general population in India.

Ola waived rental payments for drivers who leased their vehicle through its subsidiary Ola Fleet Technologies, and offered drivers the opportunity to return cars under their lease programs. Although the central government had announced a loan moratorium, drivers who had payments due on loans or leases from non-banking financial companies and informal lenders were unable to access this as not all institutions were following the central bank’s guidelines around pauses on payments, meaning workers were faced with payments they could not afford.

The Future of Platform Work

Such piecemeal measures have prompted several questions around the evolving nature of gig work and platform work–how are platform business models codifying certain work practices? How would the fungibility of workers be affected as jobs are increasingly broken down into discrete parts? How is essential work being defined and what does this mean when priority is given to relatively wealthy customers who can afford these services as opposed to the workers who have few alternatives?

For some workers, for instance those on specialized home services or care work platforms, who are typically trained and vetted professionals, the impact could play out differently. With social distancing rules in place, these workers have been left with no income. Airbnb hosts find themselves in a similar situation. Platforms offering these and other non-essential services may not recover from the crisis in their current form. How customers and platforms will react even when social distancing norms have eased is anybody’s guess. One possible outcome could be an increase in low-wage work on platforms as companies rush to fill the gaps left by this pandemic, while medium-wage work performed by medium-skilled workers disappears from platforms, widening the gap between low and high wage work, exacerbating existing inequalities.

One possible outcome could be an increase in low-wage work on platforms as companies rush to fill the gaps left by this pandemic, while medium-wage work performed by medium-skilled workers disappears from platforms, widening the gap between low and high wage work, exacerbating existing inequalities.

Even before the crisis, platformization had led to large-scale underemployment and deskilling of labor. Workers with certificate degrees and higher levels of education opted for low-paid gig work as jobs that match their qualifications were already shrinking. If these middle-skill jobs disappear entirely, most platforms could see an overcrowding of low-wage workers and a further deskilling of labor. The absence of regulatory oversight could enable platforms to exploit and mistreat low-wage workers even more.

In countries where customer awareness about the unfair working conditions of gig workers is more mature—thanks in part to robust press coverage, more mature collective organizing efforts, and less rigid social structures—there have been instances of customers aiding gig workers. Customers who are aware of how the rating system impacts workers’ earning opportunities, may often give them a high rating irrespective, leading some to claim that the rating system is no longer an effective metric for evaluating worker performance. However, in India, customer awareness around these issues isn’t mature enough yet to allow these subversive strategies to support workers. In any case, such subversive strategies do not lead to long-term structural solutions. Platforms continue to dictate terms for both workers and customers while consolidating their position and normalizing certain practices with zero accountability.

Strengthening Social Protection for Gig Workers

To be sure, platforms are also facing considerable push-back as workers organize walkouts and collective action against exploitative work conditions that put their health and safety at risk. In the USA, Amazon workers in different parts of the country have staged walkouts and protests in the weeks following the lockdown and social distancing measures. Part-time Amazon warehouse workers were successful in advocating for paid time off—a provision that was available to Amazon workers at the management level but not to the warehouse workers who keep the business running. On May 1, workers from Whole Foods, Amazon, Instacart, Shipt, FedEx, Walmart, and Target got together to strike against poor working conditions and employers’ continuing failure to provide adequate protection in the workplace.

In the UK, an Uber driver filed a case against the transportation platform for failing to provide adequate protections after his friend and fellow Uber driver died from Covid-19-related complications, without any help forthcoming from Uber. The IWGB union in the UK sued the UK government for failing to protect gig workers and other vulnerable low paid workers through government-sponsored relief measures.

In India, the Indian Federation of App based Transport Workers organized a socially distanced, peaceful and silent strike on June 9 and 10, demanding that platforms provide adequate PPE and a revised payment and incentive structure. Workers in 12 states participated in the strike.

These strategies of worker resistance and collective action are crucial in the fight for better working conditions and protections. Government regulation aimed at holding platforms accountable is critical for workers’ well-being and safety.

The first step towards regulation would be rectifying the misclassification of workers as ‘independent contractors’. As has been widely noted, platforms exert an inordinate amount of control over workers—setting wages, working hours, controlling their behavior while on the job through algorithmic monitoring systems, and setting standards for tasks performed. In India, gig workers were included in the draft code on social security. Although a piecemeal recognition, it is still a crucial first step in ensuring that gig workers on platforms are recognized as workers. Currently, definitions of crucial terms like aggregator, gig worker, platform worker, etc. remain unclear. Nomenclature such as ‘partner’ or ‘contractor’ conceals the true nature of the employer-employee relationship that workers and platforms share. The definitions in the Code on Social Security must be made clear to disallow ambiguity that could harm workers’ claim to fair treatment.

Misclassifying workers as contractors removes legal liability from platforms and puts the onus on workers to make a choice between being able to earn money on the platforms’ terms or look for alternatives.

The absence of oversight measures and regulation allows platforms to enter into partnerships or change the nature of services they offer with few questions about the prudence of such moves. Misclassifying workers as contractors removes legal liability from platforms and puts the onus on workers to make a choice between being able to earn money on the platforms’ terms or look for alternatives. Stronger oversight over platforms is required to ensure that they provide these safety nets, even when this pandemic passes.

Of course, all platforms are not the same and do not operate in the same way. Some platforms do not intervene beyond connecting workers to the client or the hiring agent, while others may only set wages and not the hours of work or the tasks involved. Tandem Research, in previous work, has put forward a framework for the provision of prorated social protection based on the level of control exerted over workers. For example, platforms that exert low control over workers—merely matching workers to employers—should ensure adequate grievance redressal mechanisms and clear terms and conditions to ensure workers are paid a fair wage. Platforms that exert some form of control—matching workers to hiring agents, setting some terms but allowing workers to negotiate wages—should ensure some form of social protection, including grievance redressal mechanisms, paid leave, and fair wages. Platforms that exert high levels of control over workers—setting wages, hours of work, and standardizing tasks—should make mandatory contributions to workers’ health insurance, savings plans, ensure fair wages, paid leave, and adequate grievance redressal methods.

For some workers, the gig economy presents an opportunity to earn supplemental income through flexible work. The Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) in California which extends the classification of employees to gig workers has been criticized by a section of workers and employers who point out that being classified as employees will be detrimental to their livelihood in the midst of employers freezing hiring in their state. This is a legitimate concern for workers and employers and should be addressed through some form of worker reporting or prorated provisions based on working hours. However, being recognized as an employee has distinct advantages as most labor laws and worker protections are designed for recognized employees. In India, the state of Karnataka is currently working on a bill to protect gig workers along the lines of AB5—this should be replicated in other state legislatures too.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 crisis has underlined and exacerbated the vulnerability of gig workers. Deemed essential workers, they have had to continue working in unsafe conditions under threat of termination and illness, with very few safety nets. Platforms have acted to preserve their business interests, choosing to solidify their relationships with governments or other platforms over investing in workers’ well-being. Many of the relief measures announced have been poorly implemented, failing to reach workers on the ground.

Workers in the Global South already contend with fewer labor protections than their counterparts in western, industrialized nations. The platform economy and non-standard forms of work exacerbate the situation.

The economic recession that will inevitably follow the pandemic will likely lead to a further dismantling of worker protections and push more workers into non-standard work with fewer protections. It was in the aftermath of the economic recession of 2008 that the platform economy came to fruition. This economic downturn is likely to cause similar, if not more severe disruptions to the world of work to the detriment of worker protection. Workers in the Global South already contend with fewer labor protections than their counterparts in western, industrialized nations. The platform economy and non-standard forms of work exacerbate the situation.

It is imperative that governments and platforms assume responsibility for the well-being of gig workers, and implement sustainable, long-lasting measures which ensure that these workers have access to livelihoods and social protections. Social protection for platform workers needs to evolve through a combination of government regulation and pressure on platforms from workers and customers to improve working conditions. The multi-country presence of some platforms makes it difficult to regulate them. A multinational, multifaceted approach to regulating platform work is thus necessary as worker protections weaken globally as a result of the pandemic.

This article is part of our Labor in the Digital Economy series.