“People are the most important to an emperor, while foods are the most important to the people”. —An old Chinese proverb

In less than ten years, the online food industry has transformed eating habits in China.

Getting takeout food is a relatively recent phenomenon in the country. The trend started with foreign fast food franchises such as McDonald’s in the 1990s. Homegrown local restaurants, such as noodle houses and those offering regional specialties, followed suit. But it was not until the rise of online food delivery platforms that having meals delivered became popular in China.

Since 2009, when the first food delivery delivery app Ele.me appeared, the number of customers using these platforms has gone up from zero to 406 million at the end of 2018. Nearly half of China’s internet user base has ordered takeout food through apps at some point in their life (CNNIC, 2019).

As of 2018, two companies—Meituan Take-away (63 percent) and Ele.me (28 percent)—jointly control more than 90 percent of the platform-organized food delivery market in China. Meituan Take-away (hereafter Meituan) belongs to Meituan-Dianping, a mega-platform that specializes in matching all kinds of local services with customers (including restaurants, hotel bookings, etc). Meituan-Dianping went public in Hong Kong last year, and was reported to have 5.8 million registered restaurants and 2.7 million delivery workers, according to data from China’s State Information Centre (SIC, 2019). Ele.me, now a subsidiary of e-commerce giant Alibaba, had 2.8 million registered restaurants and 3 million delivery workers as of 2018 (Ele.me, 2018).

Food delivery platforms generated 471 billion RMB (approximately $66.7 billion) of revenue in 2018, accounting for 10.6 percent of the national revenue of the food and beverage industry—a sharp increase from less than 2 percent in 2015, according to SIC.

Among sectors in China’s tertiary industry that have been affected by the rise of third-party digital platforms (such as transportation, hospitality, etc.), the food delivery service has grown at the fastest pace.

Among sectors in China’s tertiary industry that have been affected by the rise of third-party digital platforms (such as transportation, hospitality, etc.), the food delivery service has grown at the fastest pace.

However, consumers’ experience of the food delivery market is only part of the picture. The platform’s economic and social impact upon restaurants and delivery workers cannot be overlooked.

For restaurant-owners, dependence on platforms can be both a blessing and a curse. Joining food delivery platforms is beneficial to the extent that the volume of orders increases, but some restaurant owners find that the commission charged by the platforms (a fixed rate for small orders and a percentage for big orders) takes a toll on profitability.

In January 2019, both Ele.me and Meituan raised their commission—Ele.me to 18 percent and Meituan to up to 26 percent. As a competitive tactic, Meituan offered its strategic partner-restaurants operating exclusively on its platform, a reduced commission rate of 16 percent. That left non-strategic partner-restaurants to struggle with a squeezed net profit margin of as low as 5 percent . Restaurant-owners also experienced an increase in operational costs if they wanted more visibility on delivery platforms, or engaged with the platform’s promotional activities.

Profound changes have also occurred for food delivery workers. The explosive growth of the food delivery market has attracted millions of young migrant workers. The image of riders on e-scooters wearing color-coded uniforms and helmets—yellow for Meituan and blue for Ele.me—has become an everyday scene across thousands of Chinese cities.

A survey on food delivery riders in Beijing carried out by us (the author and Dr. Ping Sun from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) in 2018 revealed that of all the workers surveyed, about 90 percent were migrant workers from rural areas, 80 percent were 30 years old or younger, and 70 percent were unmarried. Three out of four had joined the food delivery workforce in 2017. The dominance of young migrant workers from our survey corresponds to national statistics released by Meituan and Ele.me.

The sharp contrast between China’s decaying rural regions and the promises conveyed in the ad slogans point to a dire reality. With the slowdown of the Chinese economy coupled with the falling demand for manufacturing workers, decent job opportunities are few and far between.

Riders are either introduced to the job by friends or relatives, or through job ads. All platforms deploy the rhetoric of flexibility and quick money-making. For example, the Meituan app greets riders with messages like “take orders with liberty” and “extra money made easy.” Ele.me even places targeted ads in rural China, with words like “become an Ele.me food delivery rider, no more worries about how to get a wife and a house”.

The sharp contrast between China’s decaying rural regions and the promises conveyed in the ad slogans point to a dire reality. With the slowdown of the Chinese economy coupled with the falling demand for manufacturing workers, decent job opportunities are few and far between.

It is also common for riders to shuffle between different delivery platforms. For example, we found that nearly 80 percent of riders with 3-12 month of experience have changed platforms. Many riders told us that they shifted to the online food delivery market from traditional service jobs such as repairers and air conditioner cleaners. They treated food delivery more as a temporary, in-between job, or as a source of extra income rather than a job with a prospect.

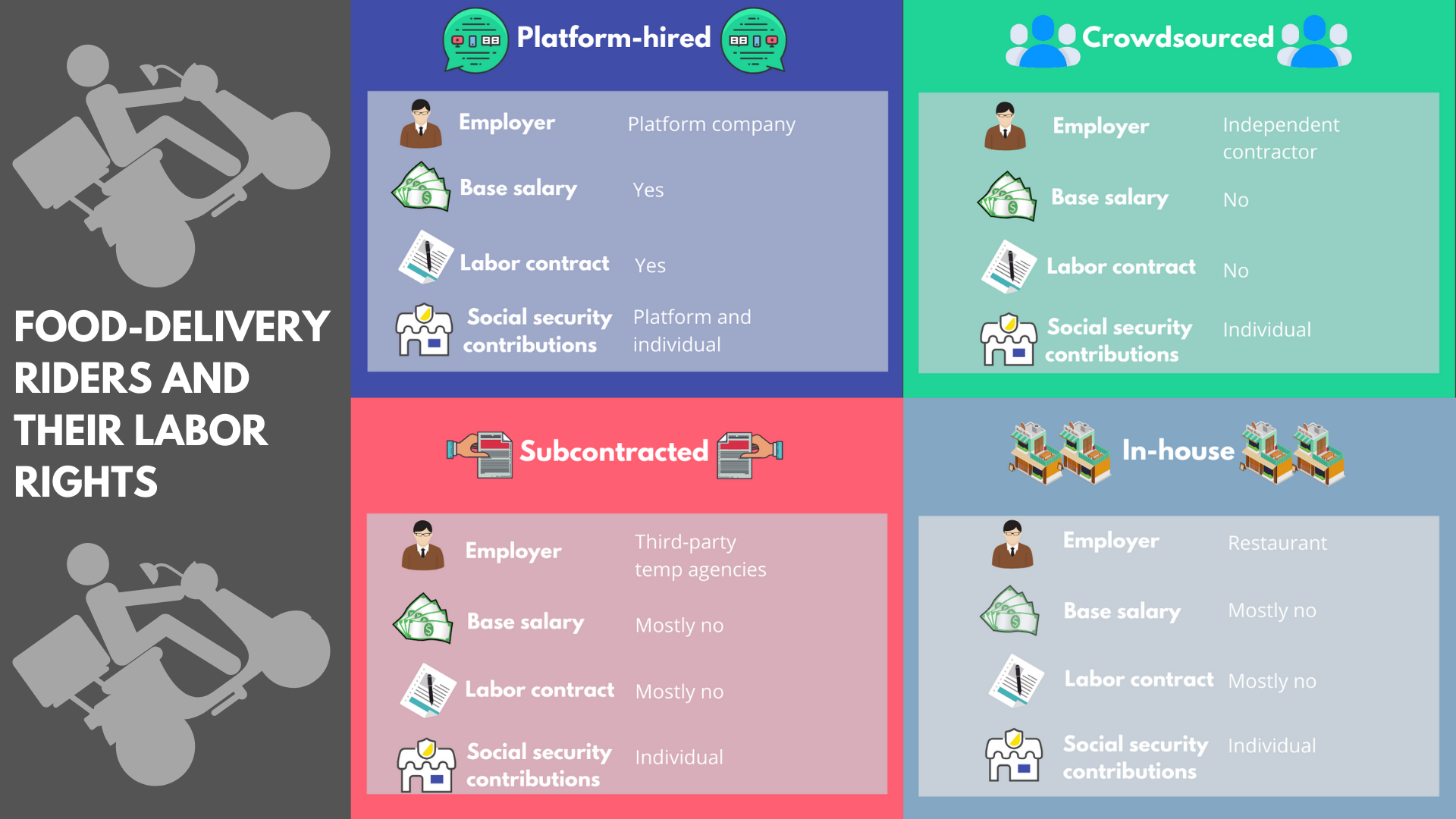

There is also a proliferation of informal employment with food delivery platforms. There are at least four different types of riders: 1) platform-hired riders, 2) crowdsourced riders, 3) subcontracted riders who are hired and 4) in-house riders. Different types of riders experience varied levels of informality and collective bargaining power.

Jiang (25, male) is representative of many riders’ take on being a food delivery worker. He says, “It was not hard to earn a decent wage last year because those platforms needed us. But as more people enter the market, the volume of orders decreases. Nowadays it is hard. The volume of orders is money. But if I find it is not worth it any more, I can always change my job.”

Their collectively disadvantageous position does not deter riders from fighting for their rights. Along with workers in the newly emerging economy (such as ride-sharing, logistics, etc.), the conditions and status of food delivery workers is among the most contentious in China. According to incomplete statistics collected by the China Labor Bulletin, from May 2018 to May 2019, food delivery workers across 19 provinces and in all four municipalities directly under the Central government have staged protests over pay cuts, low wages, wage arrears, unfair platform practices, and so on.

Since the platform-mediated food delivery industry shows no sign of slowing down, the re-intermediation power of platforms will continue to exploit workers and further undermine the autonomy of restaurant-owners. Regulations ought to address new challenges like the platform’s arbitrary power of price-setting and pay attention to the long-term neglected issues of worker protection and welfare.