Introduction

The platform ecosystem permeates our public and private spheres alike. This is reflected not just in the economy and communicative landscapes, but in the increasing use of large-scale data systems in government and governance. In a bid to platformize, public entities too have now shifted to pushing for increasing amounts of data from citizens. Digital Public Infrastructures (DPIs) are an example of this drive. In the Indian context, DPIs, as a public alternative to private platforms have enormous potential to be a public good. However, the manner of digitization and the form these initiatives take may sometimes reflect a more for-profit motivation. For instance, the thinking behind India’s DPIs is increasingly turning market oriented, stemming from a belief that creating a ‘market’ that allows the consumer-citizen a wide array of choices is the optimum way to plug gaps in welfare delivery. As a result, the only way to realize the benefits of digitization becomes to adopt a top-down approach, with for-profit entities at the helm that can enable innovation at scale and provide cost-effective services. This model tends to rely on data-extractive practices, operate in a largely opaque manner, and create governance structures with centralized power.

India’s objective with its DPIs has been to build decentralized, open, and interoperable networks, and enable innovation at scale. Within this framework, private and specifically for-profit entities, are provided in-roads into welfare services. The digitization of critical services, such as access to welfare services, healthcare, and digital payments have placed non-state, for-profit actors at crucial nodes of various ecosystems.

The digitization of critical services, such as access to welfare services, healthcare, and digital payments have placed non-state, for-profit actors at crucial nodes of various ecosystems

How Did the Public become Private?

Digitizing public services ought to be based on citizen-centric frameworks and the objective should ideally be restricted to the public good, for instance improving access to welfare services. It is indeed curious, then, to see profit-motivated entities granted the responsibility to deliver on these promises. The privatization of digital public services alluded to here can be traced back to the rise of the Silicon Valley-bred start-ups. ‘Solutionism’, as Evgeny Morozov explains, “is the tendency [of] digital firms and start-ups to present themselves as essential to the process of solving some of the world’s greatest problems.” They argued that without the expertise that lies with them alone, and their cost-effective services, digital infrastructures would simply be inefficient.

Additionally, the absence of a profit-driven market would also limit the consumer-citizen’s ability to make rational and free choices. Another critical element of this narrative is the claim that the State cannot match the technical expertise of the private sector, and cannot operate on a model backed by network effects alone. This ties in to the larger neoliberal logic of organizing society by competition and economic evaluation. Set within this framework, the State is also reorganized around the logics of competition and enterprise.

India’s Approach to DPIs: Is the Private Sector Really Involved?

DPIs in India have undertaken a unique platform-like role. The public service provided is restricted to the provision of a network or gateway built on open APIs. Individual entities (public or private) can then build atop these networks to create independent but interoperable digital services. India Stack, at the forefront of India’s DPI efforts, is structured similarly. The services encompassing the ‘Stack’ include digital document storage, identification, digital payments, telehealth, and so on. Private entities can build their own services on top of this infrastructure. The consumer-citizen then has a wider array of choices and can ostensibly make rational decisions.

DPIs in India have undertaken a unique platform-like role. The public service provided is restricted to the provision of a network or gateway built on open APIs.

The development of DPIs (specifically those within India Stack) in India has gone hand-in-hand with the presence of iSpirt, a private, non-profit organization that has supported several projects for the government at various capacities. iSpirt relies on volunteers in order to collate and disseminate knowledge about building software products. However, the role of these volunteers changed as iSpirt went deeper into the India Stack.

The following table provides details on how iSpirt participated in India’s DPI projects.

| Digital Initiative | Responsibility | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Aadhaar | To build Aadhaar-based platforms, and duplicating the model. | The success of Aadhaar allowed a new vertical of ‘societal platforms’ to be added to iSpirt’s mandate (this eventually led to India Stack) Non-state actors (primarily volunteers in iSpirt) were, writing code and crafting technology stack, in addition to drafting policies. The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) had members from the private-sector, some of whom ended up at India Stack. |

| Unified Payments Interface (UPI) | To assist with building the UPI standards for digital payments. Some members are a part of National Payments Corporation of India (‘NPCI’). | NPCI and non-state actors could create artificial entry barriers. For instance, PhonePe received a significant benefit by obtaining early access to UPI. |

| Unified Health Interface (UHI) | To develop health stack solutions (the government put out a request for proposals, however iSpirt seems to have circumvented that red tape). | iSpirt withdrew support for UHI following irreconcilable differences. The National Health Authority did not seem to have alternatives in place. This has created several roadblocks for the roll-out of UHI. |

With the perceived success of iSpirt and India Stack, private entities were granted new inroads to DPIs. Core infrastructure and services, such as email and data centers, previously under the National Informatics Centre and Digital India Centre, were opened to the private sector as well. Boston Consultancy Group (BCG) was awarded a contract to restructure NIC (NIC provides the government with essential digital services such as email, network infrastructure, data centers, software applications, cloud services, chat platforms, security measures, and more). A similar contract was awarded to McKinsey to restructure DIC. Those engaged in the process reportedly said:

“The organization [National Informatics Centre] should proactively play with new and emerging tech; it should ideate, pilot, and scale [up] such applications…The ultimate goal is to have an organization of a batch of project managers who can drive external agencies and vendors…That’s the future of e- governance.”

DPIs and Decentralization 2.0

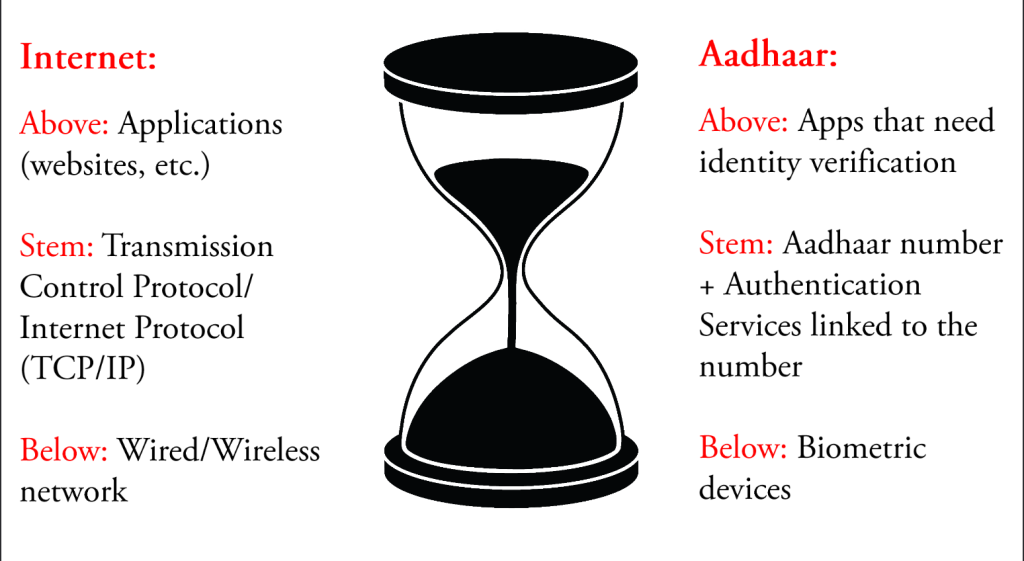

First introduced in Aadhaar, the components of India Stack have adopted the ‘hourglass model’, which centralizes control at the waist. The challenge, then, is to negotiate power between the waist and the components above and below it. The impact of such a governance structure is that there is diffused accountability, particularly when combined with a for-profit motive, in addition to the data-related and exclusionary harms that are exacerbated in private, for-profit digital spheres.

Source: Ranjit Singh, ‘From Pipes to Platforms: Designing a Country Scale Project’

The hourglass model is counterintuitive to the objective of building decentralized systems of governance. Decentralization has been cited as a building block in critical DPIs, namely India’s digital health initiative and the Open Network for Digital Commerce. While the accountability mechanism may not conform to the traditional top-down approach, it remains concentrated in the hands of select few. Within India Stack (namely Aadhaar, Unified Payments Interface, and Open Network for Digital Commerce) this group is dominated by those from for-profit sectors. The impact of critical infrastructure being platformized in this manner is three-fold. Firstly, industry standards, system architecture, regulations, etc., are directly influenced or designed by non-state actors, in India’s case through iSpirt volunteers; secondly, in the absence of a robust regulatory regime, the infrastructure will shape the law, rather than the other way around; and lastly, it is likely that private for-profit entities can establish a monopoly within the public service industry (for example, the digital payments market in India is dominated by PhonePe, followed by Google Pay and PayTM).

A for-profit service has no responsibility to mitigate exclusion-related harms. While built to reduce leakages in the welfare delivery system, DPIs in India Stack may end up creating newer leakages.

In addition to the challenges that arise when a firm controls infrastructure, the system also operates outside a social contract. A for-profit service has no responsibility to mitigate exclusion-related harms. While built to reduce leakages in the welfare delivery system, DPIs in India Stack may end up creating newer leakages. For instance, Aadhaar-related authentication services do not take into consideration the unique challenges certain groups may face: manual laborers’ fingerprints fade over the years, which result in authentication failures; migrant workers often do not have a government-issued document to replace a misplaced Aadhaar; holders of a disability card must go through the additional effort of enrolling for Aadhaar, while the enrollment facilities are not equipped to cater to them. The concerns around accountability structures take new forms, but persist.

The absence of a modern personal data protection law in India also allows them to operate without a legislative mandate, which further dilutes accountability. iSpirt, as highlighted above, was responsible for the development of UHI, an essential building block of the digital health initiative in India. However, at the last moment, iSpirt pulled out of the UHI network . Without a viable alternate in place, the roll-out of the much-touted flagship digital health program, Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission (ABDM), has been affected.

India’s digital journey has made two things clear: first, technology cannot be used as a silver bullet to improve access to welfare services. Investment in physical infrastructure and capacity building is crucial. In order to build inclusive systems, digital initiatives cannot have technology as their sole focus. In addition to investment in physical infrastructure and capacity building, governance structures are also important. ‘Openness’, ‘decentralization’, ‘citizen-centric frameworks’ are all buzzwords that have been used to conceal the increasing opacity in DPIs governance systems. The operations of the State and the technology itself become increasingly opaque to citizens. Citizens no longer have visibility over the workings of the services that they depend on. When data models determine the citizen-state relationship, it is on the citizen to ensure they are visible within these systems. In cases of authentication failures, misplaced documents, incorrect data entries, etc., the burden of correction lies with the citizen. Any incapacity to adopt DPIs, such as digital payments, identity systems, etc., will eventually render the citizen invisible to the State.

Technology cannot be used as a silver bullet to improve access to welfare services. Investment in physical infrastructure and capacity building is crucial. In order to build inclusive systems, digital initiatives cannot have technology as their sole focus.

Are there Alternatives?

The success of India’s DPIs are measured by two quantifiable outcomes—the rate of adoption by users, and the number of services on the network. India’s approach has been characterised by packaging DPIs as ‘products’. Dr. Pramod Varma, the former Chief Architect of Aadhaar, said:

“When we started in 2009, we wanted to treat [Aadhaar] as a product. That is, we should understand the incentive structures for our customer, our partners who use it, understand the whole ecosystem, activate the ecosystem to really adopt it, and it has to be what we call pull-based and not push-based products.”

It is important to note, however, that unlike the Silicon Valley-bred start-ups, these initiatives do not have venture capitalists permitting them to capitalize on network effects, and generate little to no revenue. The ability to incur losses is what would drive out the competition and allow the concerned entity to occupy a dominant position in the market.

However, digitization comes in a variety of shapes and forms. A different approach was seen in Brazil’s digital payments initiative ‘Pix’. First, Pix is funded by a State institution, Banco Central do Brasil (Brazil’s central back). The governance and system design is, therefore, determined by an infrastructure of trust. Secondly, it mandated the payment of transaction fees from the get-go. The objective was to create an ecosystem that would allow for competition and innovation within the market. While still entrenched and thereby operating in accordance to market forces, State-backed infrastructure has more responsive accountability mechanisms (including but not limited to audit systems and redressal mechanisms). The distinction reveals Brazil’s departure from aggressive transaction growth, and a focus on pricing policies that can enable long-term sustainable growth.

Technology and platforms must no longer be viewed as neutral-entities. Digital infrastructures, particularly in the context of critical services, are socio-political institutions that combine scale with necessity.

Technology and platforms must no longer be viewed as neutral-entities. Digital infrastructures, particularly in the context of critical services, are socio-political institutions that combine scale with necessity. The more people with access to the services, and the capacity to meaningfully utilize these services, the higher its social value. However, Pix is funded by a State institution, if the infrastructure is built and controlled by a private for-profit entity, the access to essential services will be strictly dependent on market forces, which are far from inclusive. Therefore, a meaningful exercise of the rights associated with decentralized, rights-based, accountable systems are contingent and will require a lot more than simply handing over the reins to non-state actors. In order to incorporate data systems in public services in an inclusive and citizen-centric manner, questions of fairness, accountability, and inclusion must be central to building DPIs.

The author would like to acknowledge Shreeja Sen’s contributions to this article.