Introduction

“Working online brings freedom – I can spend more time with my loved ones. But being a woman and running a business online is not an easy thing.”

Platform work (whether online commerce through social media, or working as a ride hailing driver) offers a promise to many youths particularly in economies where informal work is common. This research builds on existing Platform Livelihoods research by Qhala and Caribou Digital in Kenya, which explored the effect of “platformatization” on different forms of livelihood for youth in Kenya. In that research, echoing findings from global platform and labor dynamics, we learned that women still needed to overcome many pre-existing social norms and barriers in order to favorably compete with men online. Covid-19 further burdened women platform workers. Therefore, this research arose from a need to probe the gender dynamics between young men and women on these platforms.

We found three key tensions from our qualitative research (interviews, focus groups, conversations on WhatsApp groups) so far:

- Platforms offer potential empowerment, namely financial and social independence, which is valued by women. Yet, for many of the women we are interviewing, this empowerment comes with narratives of exploitation, harassment by customers, and often unpaid work, along with safety and security concerns that force them to plan their movement. With social norms and gender roles at play, there are barriers to entry as well as empowerment for some women.

- There is a myth of flexibility offered by platform work. However, some women reported waking up at 3.00 am to accommodate domestic and platform work in their days. While male interviewees believed gig work was a boon to women, female interviewees said it simply reflected offline biases.

- The pandemic introduced good and bad changes. In some ways, platform work (e.g., freelancing) became more acceptable as many more people began working from home online, which was previously seen as ‘not real’ work. On the other hand, many women earned less or struggled to find work or manage professional assignments with domestic work, which disproportionately fell on their shoulders. Mothers or married women had to bear this extra burden.

In this article, we share a brief overview of our landscape study of women and platform livelihoods, explore the three key tensions identified in our work, and analyze them through a Gender at Work framework:

- a brief landscape study of women and platform livelihoods

- the three tensions we have identified from the ongoing research in Kenya

- an analysis through the Gender at Work framework

Women and Platform Livelihoods

“The platform economy fundamentally benefits from the same patriarchy that has benefited prior sectors”, states Bama Athreya in Bias In, Bias Out, her report on gender inequality in platform work. She states, that “it should be no surprise to us that those things are replicated when new technologies emerge”. Some themes (and contradictions within these) that have consistently emerged around gender and platform work in the past few years include:

- Platform work seems to give women the opportunities that they may not have gotten elsewhere. A recent survey of 4,900 gig workers in 15 countries found that 11% of women said that they didn’t have a job before joining a platform, compared to 8% of men.

- However, gendered patterns of work continue on platforms. For example, women are more likely to be engaged in domestic work online than ride hailing.

- Flexibility for women is often one of the key benefits of working on/through platforms. However, often, women are pressured into juggling between paid and unpaid care work (domestic/reproductive labor).

- Platform work can make work more ‘professional’ for women but can also translate into surveillance for them. While this can apply to both men and women, cases of online trolling and harassment are more likely to happen to women than men.

Themes and Contradictions in Kenya

Initial findings from our research in Kenya indicate three major contradictions: Empowerment, flexibility, and the penetration of social norms to online platforms.

“I feel empowered…but you have to have a thick skin”

Fiona is a single mother who sells fried bread and other snacks online. She uses WhatsApp for Business, Twitter, and Facebook to market and sell her products. Covid-19 helped accelerate her business because more people were ordering food online. Fiona credits the flexibility of the work for allowing her to earn an income while caring for her two children. Her day begins at 3:00 am, when she does housework and a little later, wakes her children up for school. After the school bus picks them up at 6:00 am, she gets to work. In between cooking, she checks orders and social media every three hours.

“Working online brings freedom – I can spend more time with my loved ones. I have earned respect, I feel better about myself, I feel more independent, I have learned discipline”, says Fiona. But later, she adds “Being a woman and running a business online is not an easy thing … it can honestly be very, very heart-breaking and one must have or develop a thick skin.” Fiona speaks of being trolled for her prices. “They [followers on social media] will be like, you know, these women, they’re just selling overpriced products, because they’re beautiful, and they expect we will buy because, you know, they have the good looks”, she narrates.

When other women were interviewed across different sectors, they too reported similar contradictions in the empowering potential of platform work. Women who rented out Airbnb properties or rooms within their houses stated how it had given them the opportunity to earn an income. However, they also elaborated that they had faced harassment, for example, when meeting a new guest, or when guests asked for something to be fixed but behaved inappropriately. Esther, a female Airbnb host, stated that she had now adjusted against this kind of inappropriate behavior by hiring someone else to meet her guests and minimizing guest interaction. However, female Airbnb hosts also stated that they often had full support from Airbnb when they reported such interactions.

Platform work may ‘empower’ but only to a certain extent and women often self-impose limits on their freedom and empowerment, in alignment with social norms.

Similarly, the few female delivery drivers we spoke to stated that they were careful about certain locations, turning down jobs that were after dark, or too far from home. Platform work may ‘empower’ but only to a certain extent and women often self-impose limits on their freedom and empowerment, in alignment with social norms.

“In the end you’re still a woman”: The myth of flexibility

Often, using platforms means working from home, a departure from the traditional office work in Kenya. We wanted to understand what this means to women working on platforms.

The myth of flexibility is often associated with ‘platform empowerment’. While platform work affords a woman the opportunity to work from home, flexibility often means a ‘double shift’. Jenks, a freelance transcriber who works at night, lives with her partner, Peter who is also a transcriber. She is the one who has to do the housework around her paid work. She states that, “at the end of the day you are still a woman and have to look after the house because that is how it is”.

Flexibility in many cases increases women’s burden as they are expected to fit in paid work alongside domestic work simply because it is the same environment.

Other women reported the challenges of managing a home, often missing out on work because they simply were not online at the time. This also relates to the impact of algorithmic bias against women, though we could not sufficiently research this. Flexibility in many cases increases women’s burden as they are expected to fit in paid work alongside domestic work simply because it is the same environment.

The pandemic is slowing challenging social norms

Echoing Athreya’s statement on patriarchal bias in platform economy, a female gig worker in Pakistan said, “I thought freelancing and entrepreneurship were empowering women – which they are, certainly – but they are changing nothing about the society and the culture we live in”, she concluded. Social norms are considered to be static for the Pakistani gig worker. However, in our research, while there were many voices such as Jenks, we also found social norms were slowly being questioned, and Covid-19 played a role in this.

Pre-pandemic, some women reported that working from home was not seen as a ‘real job’. It was either seen by families as something providing pocket money or even something suspect or shady. During the pandemic, as more people began working from home, families became more accepting of platform work, including husbands of their wives.

In the words of Ella, an academic writer, “The perceptions, I think, are slowly changing. Yeah they are, because people have now started seeing the benefits of online businesses especially after Covid. You know after Covid hit because almost everybody started moving to online businesses so they see that there is some potential in it. They stopped having so many negative perceptions about it especially towards women. The negativity is still there but it’s just gradually changing.”

Applying the Gender at Work Framework

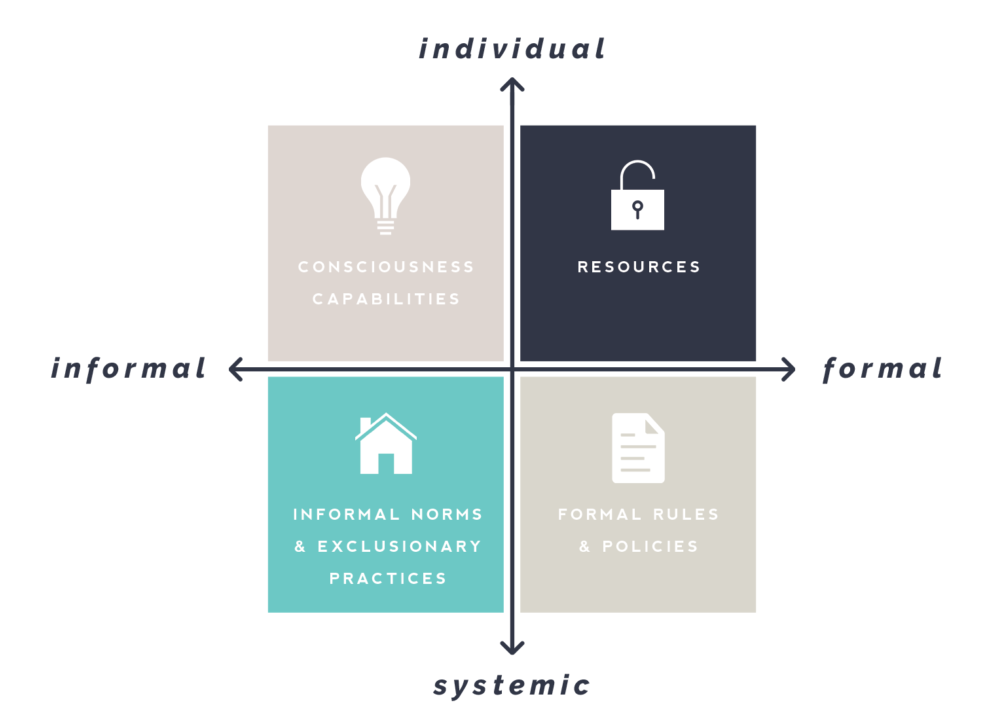

Several frameworks have been proposed to analyze gender empowerment, including the UN’s Gender Related Development Index and Gender Empowerment Measure (both as part of the Human Development Index) and the Gender Equality Mainstreaming framework. In her paper “Women’s Empowerment: What Works?”, Andrea Cornwall presents another accessible Gender at Work framework. The two-by-two framework states that change can be institutional/systemic or individual; it can also be formal or informal. The framework suggests all these factors are enablers (or not) to empowerment. The interrelationship between gender equality, organizational change, and institutions or ‘rules of the game’ is held in place by power dynamics within communities.

Source: Gender at Work framework

Under this framework, true women’s empowerment transcends mere facilitation to access assets or providing enabling laws and policies. It includes overturning limiting normative beliefs that leave women dependent and subordinate, challenging the restrictive social norms, and contesting everyday life institutions that sustain gender inequality.

If we apply this to some of the experiences above, it seems that some change (empowerment) is happening on the top right-hand side of the framework in relation to the findings from Kenya but change is slow on the left-hand side (consciousness and informal norms) as well as bottom right (formal laws and policies). For Jenks, for instance, even though platforms have given her the flexibility to work from home, restrictive gender norms that tie her to care work limit her from achieving her potential on the platforms, unlike Peter. One platform worker spoke of a couple who were freelancing with a child while supporting each other in doing the housework, and wished she had the same. “The woman is the one who wakes up early, looks for the jobs and goes back to sleep. When the husband wakes up, he starts writing. They are able to save time and work together. Maybe if I had such an experience, it would have been easier for me”, she said. Perhaps this also suggests that social norms are slowly changing.

The Gender at Work framework includes overturning limiting normative beliefs that leave women dependent and subordinate, challenging the restrictive social norms, and contesting everyday life institutions that sustain gender inequality.

Social norms are also very context specific. Just because a woman may be public facing in her platform work, does not mean she has freedom in her private life. This became apparent when we asked three women in our study to self-shoot videos of themselves and their lives to tell us their stories as platform workers. Daisy was one of these women. Daisy’s husband was happy for her to work as a delivery driver (even through her pregnancy), which meant interacting with strangers in her daily life. However, he was unhappy about her participation in the video aspect of the research. When he found out, he confiscated the equipment, demanded that she stop filming, stopped her from working and eventually sold the bike he had bought her to start this work in the first place. Video was too intrusive of the home, whereas delivery driving was acceptable as it was outside the home. This example illustrates how empowerment is precarious and constantly negotiated.

Finally, changing social norms is made easier when the path is charted by others. Ella posits that societal expectations still stand and women are still expected to abide by them but her brother’s experience as an online writer helped:

“My dad, he understood because my brother had already been into that line, so he knew exactly what the job entailed and he was supportive because it’s a way of earning money, reducing expenses for the family so he was supportive of it but other people are usually so blunt and ignorant. They are usually like, you work online, you work all day, will you even get a husband? Very very weird comments, when you say you are an online writer.”

Summary

“A man would have been treated normal, they would have said that, that is part of life and I don’t know why the society stereotypes women, we are all human beings, personally I can’t stereotype my children by telling them that a woman is supposed to do this and a man is supposed to do this, I even told my dad it reaches a point where one has to go out and look for a job and especially us as women who are married you can’t all the time call your dad telling him to help you, it will not portray a good image in the society so they had to accept what I was doing.” – Lyn, motorcycle driver

Lyn’s quote illustrates some of the tensions that the workers we spoke to were facing. While much literature on women and platform work discusses labor injustices, we also need to keep in mind social norms from family and friends (the left-hand side of the Gender at Work framework). Platform work is not equal. There are barriers to work way before a woman joins any digital platform and we need to discuss these.

While women platform workers may believe that platform work empowers them to some extent and feel a sense of freedom, they are still at a disadvantage from informal norms or formal rules and policies.

Our research is still ongoing. We are yet to discuss findings from the primary research in Ghana and Nigeria. Our early findings from Kenya illustrate the dissonance between some of these quadrants of the Gender at Work framework. We found that while women platform workers may believe that platform work empowers them to some extent and feel a sense of freedom (consciousness, capabilities), they are still at a disadvantage from informal norms (“at the end of the day, I am still a woman”) or formal rules and policies (legal support against harassment, for example). Platform work is often seen in terms of binaries (empowering or exploitative) but our research suggests that empowerment is nuanced and constantly facing challenges. These social norms can be challenged in multiple ways as part of the larger feminist vision for the digital empowerment of women workers – supportive laws and policies are one way to achieve this. However, social change, outside the platform workplace, is just as important.

This article is based on ongoing research conducted by Qhala in Kenya, as part of a three-country project undertaken by Caribou Digital in Kenya, Nigeria (Lagos Business School) and Ghana (University of Ghana), in partnership with Mastercard Foundation.

This article was co-authored with the following collaborators: Fred Mucha, Ann Wambui, Shikoh Gitau, from Qhala and Grace Natabaalo from Caribou Digital.