The current Big Tech infrastructure poses a threat to labor security, accruing job losses, displacement, and even direct dispossession in many instances. An Oxfam report states, “The oppression of women across the globe is most keenly felt among the working class, with an average wage 24% less than men, longer working hours, and twice as much unpaid care work undertaken.” The worst-hit is the Global South, where 75% of women in the working populations are employed in the informal economy, possessing little, if anything, in the way of employment rights. In the context where the crisis in care infrastructure was acutely felt, a lot of workers across the world have found themselves occupying unprotected and precarious jobs. While social spending in the Global South is systematically reducing, we also see an intensification of women’s care work burdens. This presents us with a new reality, where the historic gains for women’s economic participation have been eroded to a degree where women workers, particularly those in the Global South, find themselves being expelled from the labor market. This has directly resulted in the widening of the gender poverty gap that goes beyond the visible symptoms of the gender digital divide. It is increasingly evident that frontier digital and data technologies will play a critical role in “building back better”. However, in its current shape, the financial system is under the stranglehold of Big Tech, which dominates digital value chains. Economists and investors glibly view a Covid-19 “K-shaped recovery” as a hopeful economic development, where certain sectors recover quickly while others continue to lag, resulting in high unemployment and automation of work across the globe. Notably, this economic recovery graph will not benefit the world’s most marginalized women, especially those in the informal sector.

Against this backdrop, a panel discussion was organized at the NGO CSW66 Virtual Forum on 15 March 2022, seeking to address what it would mean to recover feminist futures of work. To address this issue, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung initiated The Future is Feminist, a project that brings together feminists from across the world to develop critical economic perspectives. Based on the findings of a working group of feminist organizations and activists who worked together over one and a half years, the project created amongst others, a framework document for action titled, ‘The Deal We Always Wanted’. Some of the key ideas in the framework document on furthering women’s empowerment and gender equality in rapidly digitizing global digital value chains, have been taken by IT for Change into policy debates at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). All our conversations with the UN, henceforth, hinge on three prongs: i) making Big Tech accountable, ii) having a binding global digital governance paradigm at the multilateral level, and iii) building public data infrastructures towards catalyzing regional dialogues that would lead to an evidence-based global campaign on “A feminist UN agenda for innovation and technological change”.

Our sustained efforts and engagements through 2021-22, culminated in the 66th Session of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW66) Virtual Forum held in March 2022, where the spotlight was on “Women’s economic empowerment in the changing world of work”. This online discussion explored questions on feminist futures of work in the digital epoch, by examining policy and programmatic actions that are needed at the global, national, and local levels to ensure women’s economic empowerment pathways expand in digitalizing value chains. The discussion also highlighted the roles and responsibilities of the UN, governments, private sector, and civil society in making this possible.

The historic gains for women’s economic participation have been eroded to a degree where women workers, particularly those in the Global South, find themselves being expelled from the labor market.

We were joined by Emilia Reyes, Co-Convenor of the Women’s Working Group on Financing for Development, and in that capacity, co-lead of the Beijing+25 Economic Justice and Rights Action Coalition; Karishma Banga, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies (IDS); Marina Durano, Adviser on Care Economy and Partnership Engagement, UNI GLOBAL union; and Isabelle Durant, Deputy Secretary-General, UNCTAD. This virtual forum was designed to tackle the gaps in economic policies that have been reflected in the setbacks faced by people in general, and women in particular, in the aftermath of the pandemic. At the outset, the panelists agreed that it was insufficient to merely tweak and readjust algorithms to close in on gendered digital sociality, as it serves little to include women in an adversarial and fundamentally unequal digital economy. It is essential for a feminist future to not only “analytically include” women in an unequal global system but rather, for women to truly be liberated, the systemic collusion between financial and digital capital must be upended by the people! In line with this, the panel was invested in envisioning the imaginaries of a feminist future where women’s rights would be at the heart of economic development.

At the panel discussion, Anita Gurumurthy, Executive Director of IT for Change, began the conversation by stating the urgent need to reorient digital governance models towards social transformation, recognizing the state’s function in providing public services and protecting public goods. She implored us to recognize the digital as more than a mere instrument for enhancing productive capabilities in the present political economy. A broader understanding of digital technologies would help us grasp the constitutive remaking of society, engendered by data and intelligence capitalism. The digital-as-an-instrumental-phenomenon exceeds the framework of being the latest means of production, it has the potential to become a handmaiden and lever of big capital unless we take back control from totalizing state power and corporations.

Data, artificial intelligence (AI), and platforms are powering capitalism today by lending it the infrastructure to expand. The modus operandi of data and intelligence capitalism is to give a competitive advantage to first movers in the industry, who then have internal contestations over hegemony on data which has been monopolized by Big Tech. The monopoly rents generated through control over network infrastructure which accrues value for Big Tech behemoths, currently concentrated in the United States, places the countries from the Global South in a perilous situation. Such a mode of rentier capitalism fundamentally excludes people and nations with limited resources from having any claim to the data that is collectively produced. In addition, Gurumurthy reiterated that the pandemic is but a grim foreboding of the many ominous consequences that are bound to follow from a growth project gone awry, with a cavalier disregard for planetary boundaries. As has been widely documented, the pandemic, simultaneously presented a window for aggressive penetration of data technologies into the Global South.

To understand the broad contours of both productive and reproductive labor, Emilia Reyes, Co-Convenor of the Women’s Working Group on Financing for Development, urged us to broaden the questions on the economy. Women’s labor is more likely to be unpaid and informal, placing them in particularly precarious positions in terms of human rights, opportunities, income, social protection, and wellbeing. She turned our attention to how women from the Global South labor under precarious conditions to produce the majority of commodities and services that fill up the Global North’s treasury. She asked us to reckon with the reality that data colonialism continues to expand through international trade corridors in the most unassuming ways — oftentimes, deploying the vocabulary of aid that surreptitiously conceals capitalist interests under the guise of philanthropy. Therefore, digital development in a feminist future cannot obscure the neo-imperial policies underscoring the financial system. She also cautioned us to remain mindful of the strategic spaces that have emerged as spaces for international dialogue, promising to bring the world under one roof, raising concerns about the narrow focus on multistakeholderism.

Emilia Reyes speaking at the Virtual Forum. Her paper on a feminist green New Deal can be found here.

While the pandemic-induced crisis and digitalization have displaced women from the labor market, we also see women being catapulted into the digital economy as entrepreneurs, content creators, and service providers in new forms of flexi-work and remote work. In this context, Isabelle Durant, Deputy Secretary-General of UNCTAD, suggested that flexibility and stable employment need to be balanced while acknowledging that jobs that don’t offer social protection are no jobs at all. With 13 million fewer women in employment in 2021 compared to 2019, 57% of the jobs likely to be displaced by digital automation by 2026 belong to women, and there are significant gender gaps in what are classed as “skills of the future”. Within this new paradigm, digitalizing value chains in manufacturing and services sectors have recalibrated value distribution to further advantage developed countries, wealthy corporations, and tech giants. Amid this backdrop, a business-as-usual approach cannot work. Durant emphasized that women need greater access, control, and ownership of their own data in order to upskill and have mobility into high-value growth propositions. She also presented the UN action roadmap for women’s labor to be valued in the market after a post-pandemic retreat. In order to prevent the increasing precarity of women workers worldwide, she proposed that policy interventions be hinged on digital skill-building, greater access to credit, data ownership, better social protection, and envisaging a regulatory role of the state in governing data flows. She recognized that women need greater access to credit to be able to scale up their projects and therefore, it is imperative to have an action plan for digitization which would, in turn, help education, health and not just remain limited to e-commerce.

We need to regulate data flows at regional and national levels such that the unbridled free market does not strip the social producers of data of their stake in decision-making. In this regard, Durant also accepted that the UN is institutionally constricted as member states from the Global South stand internally segmented and differentiated. She accepted that it is neither possible nor desirable to bring all nation-states into the UN field while simultaneously reaffirming the need for a unified platform to address global issues concerning ecological crisis and international financial economy. Thus, turning our attention to the need for building commons – a public place to challenge digital enclosures and their systemic potential for global negative impact. A candid Durant admitted, “The UN system is under threat today, so where would these conversations take place? The systematicity of the system is where we need to intervene politically.”

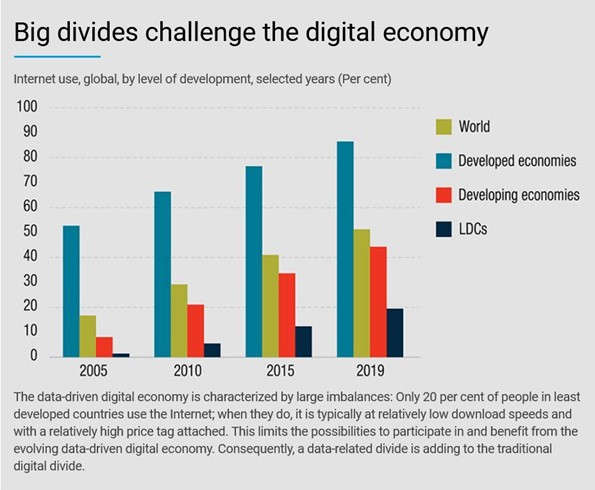

Digital Economy Report 2021

Automation, digitization, and casualization of work have become the most identifiable markers of a digital capitalist paradigm. Current trends in this paradigm reveal that women workers from the Global South are unable to benefit from the new digital and data opportunities due to structural constraints. Instead, they endure systematic exploitation, as well as job losses and unfair terms of participation. How should such digital value chains be restructured for a gender-just global economy? What new paradigms of industrial policy do we need?

Karishma Banga, Research Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, reiterated that the digital divide goes much beyond binary access to technologies between men and women. She highlighted how the divide occurs at three levels: at the individual level (in terms of access and adoption), at the firm/sector level (in terms of technology adoption by women-owned firms and participation in the ICT sector), and at the economy level (in terms of economic dividends and decision-making). Even if women in the Global South have the same access to digital technologies as those in the Global North, there is a persistent digital divide in the adoption of digital technologies for productive purposes. Citing her study, Karishma pointed out that the digital gender divide is not caused by negative attitudes towards new technologies, but rather, due to lower enrolment in primary and secondary education, lower technology literacy, lagging physical infrastructure (electricity, postal competence, etc.), and higher internet costs. The lower involvement of women at all levels — from skills and agency to ownership of technologies — is a potential contributory factor of the digital divide, that is, in the economic dividends reaped from the use of technology. Data from interviews with 31 African businesses, mostly MSMEs, revealed that women-owned African firms tend to sell through their own websites, either via an e-commerce-enabled website or through online contact forms. Lower participation of women sellers on third-party e-commerce platforms in the Global South could partly be explained by lower access to credit and financing, making it difficult to afford the higher commissions charged by these platforms, information asymmetries, and training gaps. Interview data from (mostly women-owned) MSMEs further reveals that the development of e-commerce-related websites, their maintenance and repair at reasonable rates, and enabling the integration of these websites with online payment solutions, such as M-Pesa, remain obstacles for e-commerce uptake in African countries.

Karishma Banga speaking about her study at the Virtual Forum.

Feminists from the Global South have long recognized that the care crisis and labor exploitation are two sides of the same capitalist coin, in that care is both non-valorized labor as well as necessary/invisible source of surplus value under capitalism. In the digital economy, this problem comes into sharper focus with the simultaneous gig-ification of the entire economy and the dismantling of permanent employment with its social protection cover. What has happened to the social contract, as we knew it, in the “fierce” new age of Big Tech? What does social justice in a digital world look like? Marina Durano, Adviser on Care Economy and Partnership Engagement, UNI GLOBAL union, believes that regulatory frameworks are constantly lagging behind technological innovation. Therefore, we are unable to wrest the risks and opportunities offered by the current developments in the digital landscape. We need to reckon with the reality that we are not only challenging Big Tech corporations but embedding these concrete losses of historical gains in the global financial system. The tech industry is deeply embedded with financial capitalism, with venture capitalists riding their money on HealthTech, FinTech, EduTech. These companies are flourishing at a time of global crisis. She highlighted the enclosure movement by financialization and digitization to capture data markets, which is engulfing the intangible commons through privatization. With more and more users coming to the web to access care and look for a community of support, it is important that we see the internet not just as an instrument of care but as an infrastructure that needs design interventions. As Big Tech abdicates its end of the social contract and transfers these burdens to resource-starved states amid the economic crisis brought about by the pandemic, how should the labor and feminist movements respond? There is limited trust in UN multilateralism but at the same time, there is an aspiration for universal dialogue. Systemic crises such as climate change and the pandemic cannot be challenged at local levels alone. Indeed, countries are geopolitically divided yet, it is important to ask why universality cannot be achieved in the existing system? Not only are countries divided politically but also the platforms where they aggregate represent political interests of the stakeholders that leverage the gains of global engagement. Multilateralism needs to be rethought along with digital commons. While it is true that all nation-states need to come together, we must also not be oblivious to the fact that there is massive inequality between nation-states and therefore just sitting across the table from each other does not level the playing field. Every time countries come together, the agenda is steered by big powers against the commons-ification of capital.

With more and more users coming to the web to access care and look for a community of support, it is important that we see the internet not just as an instrument of care but as an infrastructure that needs design interventions.

-Marina Durano

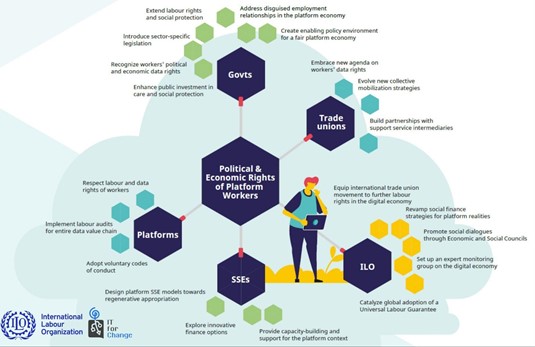

Source: IT for Change’s report on Platform Labor in Search of Value, pg.64

Durano’s call for action included the need to align the digital-financial and care economy to reduce the contradictions among and between them which will come by ensuring that new innovation and apps don’t end up becoming assets for the future for private companies. If we want to ensure public interests are protected, then we need to intervene and make sure that platform infrastructure is not commodified and privatized.

There is a pressing need to make a clean break with the current techno-capitalist paradigm and work towards a new digital economic future that serves human rights, social justice, and gender equality. This includes attempts at increasing women’s mobility to move to higher value segments of digital value chains, invest in public data infrastructure, and arrive at a binding global normative consensus on the governance of platform, data, and AI technologies grounded in an integrated and indivisible imaginary of human rights that ensures dignified social existence.

You can watch the complete talk here.