China, in the past decade, has witnessed an exponential growth in the number of internet users. According to the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), as of June 2021, the number of Chinese internet users had reached 1.01 billion. Internet users between 10-19 years of age account for 19.6% of the total number. They are also one of the most active groups online, especially on social networking platforms. Smartphones give adolescents convenient and unsupervised internet access, which might facilitate ‘online sex-seeking behaviors’ or ‘internet-based sex-seeking behaviors’. An online survey about sex-seeking on the internet and mobile-based applications among Chinese youth, indicates that nearly a quarter of participants who had had sexual experiences sought sex online, and online sex-seeking for the first time was highest among youngsters aged 15–24 years. Many of their sexual experiences could be categorized as high-risk sexual behaviors.

One of the most effective interventions to prevent any health risk and violence associated with high-risk sexual behaviors is Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE). It is a curriculum-based process that includes scientifically accurate, age-appropriate education about human rights, sexuality, gender equality, relationships, and sexual and reproductive health rights using a non-judgmental approach.

In this context, this essay analyzes the challenges around the changing sexual behaviors of youth and sexuality education programs in the digital era in China. It explores how the rapid growth of the internet in China has changed the conceptions around sexuality and how sexuality education programs have been adapted to meet the changing needs of the youth. In particular, we focus on the gap between the need for sexuality-related information and the lack of a school-based comprehensive sexuality education curriculum. It is also essential that the paradox between censorship and self-censorship of sexuality-related media content and the booming market that profits from erotism and sexuality, be unpacked. We contend that a feminist analysis is essential to understand these complex phenomena in the digital era and strategically respond to state regulation and marketization of bodies and sexuality by private actors.

To do this, we draw upon two areas that we have researched in the past – an online survey on sex-seeking via the internet and mobile-based applications among young people in China; and CSE programs and related policy advocacy in China. We apply a hybrid research methodology, which combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. Our quantitative data is based on a survey conducted by the China HIV/AIDS Information Network (CHAIN) in 2017. The qualitative data is from interviews with leading scholars, advocates, and educators in China, who have worked to promote CSE in the past decade.

Gaps and Paradoxes in Sexuality Education and Information

Globally, internet and mobile phone use among the youth is higher than the other age groups and the number of young users is steadily increasing. In China, the prevalence of online sexual activity, including sharing sexually explicit material, seeking sexual partners, engaging in cybersex, and flirting is high. In this scenario, CSE is essential for young people to be able to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, and sexually transmitted infections; to promote values of tolerance, mutual respect, and non-violence in relationships; and to plan their lives. In China, official documents usually use ‘sexuality education’ or ‘health and safety education for adolescence’ instead of CSE as evidenced through several references to sexuality education in “Outlines for Child Development in China (2021-2030)”, launched in September 2021. A review by UNESCO of 87 comprehensive sexuality education programs, including 29 in developing countries, found a number of positive outcomes such as delayed initiation of sexual intercourse, decreased number of sexual partners, increased use of condoms, and decreased sexual risk-taking. However, it is important to note that none of the Chinese sexuality education programs were part of this research, even though some pilot CSE projects in China have revealed similar results.

CSE not only offers a more comprehensive curriculum on sexuality-related issues, gender equality, rights, and health, but also capacitates the youth to deal with issues of discrimination, violence, and other challenges they may encounter both online and offline.

Despite educators’ and advocates’ efforts to promote CSE for children and adolescents in school curricula, sexuality education has always been controversial in China due to the sensitivity of the topic and rigidity of school curricula. However, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the acceptance of e-learning and online education, which catalyzed the growth of sexuality education programs on various online platforms, such as WeChat, Sina Weibo (a Chinese online platform similar to Twitter), e-learning platforms, etc. This allowed sexuality education programs to reach audiences that could usually not be reached physically or in a classroom, such as parents, out-of-school youth, and the general public.

Meanwhile, censorship by governments and platform companies, commercialization of education, and prevailing misogynistic and anti-feminist sentiments have made online sexuality education extremely challenging. For instance, just as in the case of mass media, content on the internet that contains information on sex and sexuality has always been subject to draconian censorship laws by the Chinese government, media organizations, and platform companies, which also results in people engaging in self-censorship.

Censorship is often done in the name of upholding morality and protecting children and youth from “contamination” via detrimental information, which usually refers to pornography, but also sometimes includes content concerning gender non-conforming identities, non-normative sexualities, and sexual minorities. A case in point: In July 2021, dozens of WeChat accounts with content related to issues faced by the LGBT community were suspended or removed from the platform. Most of these accounts were managed by university students and volunteers for the purpose of sexuality education. On the other hand, topics on sexuality and intimacy are the most visited on the internet, because of the youth’s mammoth demand for such information. Furthermore, despite the moralistic and protectionist rhetoric and censorship, erotism, promises of improving sexual pleasure, and even self-identified dating coaches or ‘pickup artists (PUA)’, have become lucrative businesses that proactively seek their clients through online platforms and apps that target young people.

Changing Sexual Behavior of Youth and their Unmet Needs in CSE

The past few decades in China, especially the 21st century, have witnessed increased awareness and recognition of people’s sexuality and its diversity due to the “reform and opening-up” policy launched in the late 1970s. National survey data suggest that the prevalence of multiple sexual partnerships, extra-marital sex, and casual sex (sexual activity between people who are not established sexual partners or do not know each other well) increased significantly in the last few decades, and sexual identities, norms, and practices became more diverse among men and women, young and old. Meanwhile, the debates around gender and sexuality have exploded in public discourse, particularly on the internet and social media, including via blogs and WeChat. Furthermore, public opinions about issues of pornography, sex work, sexuality education, sexual orientation and gender identities, masculinity and femininity, marriage, procreation, etc., have been extremely divided.

Globally, digital media increasingly influences the lives of young people and their way to explore sexuality and access to sexual and reproductive information and services. In Asia and the Pacific, a survey conducted by the United Nation Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2019, discovered that young people use digital media for creating, sharing, and accessing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) information; building communities and accessing SRH support; exploring sexual norms and identity; and forming and exploring intimate relationships.

The online survey conducted by CHAIN from September to November 2017 in China, reveals that young people actively use the internet and social media to express, learn, and experience their sexuality. Among 8,871 eligible survey participants (3,938 male and 4,833 female), 1,177 people (752 males and 425 females) claimed to have engaged in online sex-seeking. Of these people, 591 are between the ages of 20 and 24 (accounting for 50.22% of the total figure) and 139 are between 15 and 19 (accounting for 11.81%). Besides posting and live streaming on social media apps and networks, young people are also using short video hosting, music, e-commerce, and gaming platforms for sex-seeking. Compared to females, males reported more sexual experience and online sex-seeking.

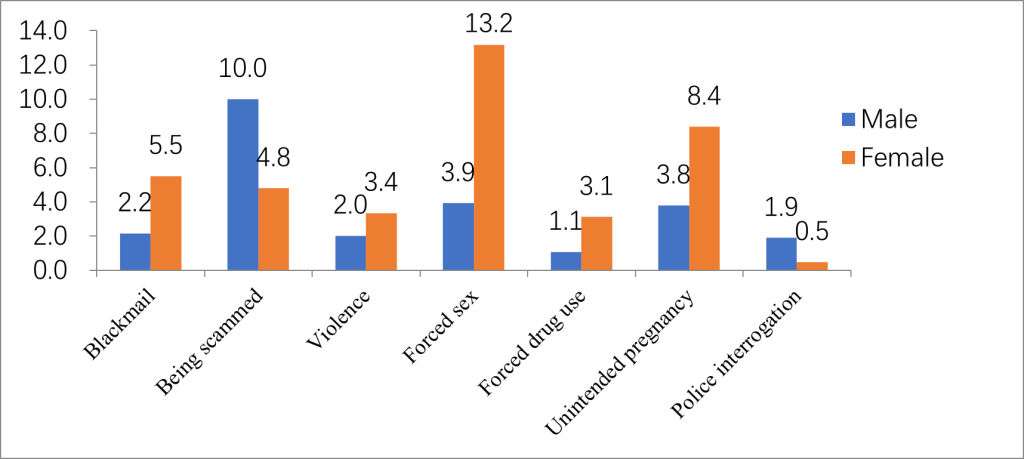

However, due to poor access to CSE and lack of media literacy, including digital media literacy, many youngsters are forced to engage in unprotected sexual activities, which are often initiated online and increase the risk of sexually transmitted diseases like HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, youngsters also reported other negative experiences. This included being blackmailed, scammed, and being subjected to violence such as non-consensual sex, forced drug use, unplanned pregnancies, police interrogations, etc. As the figure below shows, males when compared to females, are more likely to be scammed and experience police interrogation. However, females are more likely to experience blackmail, non-consensual sex, forced drug use, and unintended pregnancy.

Bad experiences of online sex-seeking (source: CHAIN)

Regrettably, this online survey did not question whether these young people had received sexuality education, as well as when and what kind of sexuality education was applicable to them. Nevertheless, in terms of public health concern, such as in the context of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and HIV prevention, the topics on sex and sexuality are not reckoned as taboo and subject to censorship. However, this kind of framing of sexuality has resulted in moralizing sexuality and limiting what is considered the ‘appropriate’ kind of information to be provided to youth in the name of sexuality education. For example, China’s “Children’s Development Program (2011-2020)” had promised “to integrate sexual and reproductive health education into the curriculum of compulsory education”. Prior to this, the AIDS Prevention Education Project for Chinese Youth was launched in 2006, with an aim to establish “Qing Ai Xiao Wu” (Youth Love House) in universities, primary and secondary schools, and kindergartens to promote HIV/AIDS prevention, sexual health, mental health, public interest awareness, and Chinese traditional culture within the education system.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Education established an expert group on AIDS prevention in education. The expert group released a consensus document in July 2021, promising to impart age-appropriate education on sex-related ethics, responsibility, and laws, risks associated with unsafe sexual behavior, and guide students to establish a progressive and healthy view of sexuality, marriage, and relationships.

However, as mentioned before, CSE not only offers a more comprehensive curriculum on sexuality-related issues, gender equality, rights, and health, but also capacitates the youth to deal with issues of discrimination, violence, and other challenges they may encounter both online and offline. Furthermore, it should be noted that many CSE programs and educators take advantage of such government initiatives and public health rhetoric to integrate more comprehensive CSE content into their endeavors.

CSE in the Digital Age: Reflection from Educators and Advocates

The findings of the CHAIN survey make it apparent that sexual behavior of young people and their method of accessing sexuality education has changed in the digital era. A survey conducted by the UNFPA in 2019, in which 1,432 youngsters between the ages of 15-24 from across Asia and the Pacific participated, found that around half of them identify the internet and social media as one of the most important sources of information about sex. In such a context, how can CSE programs effectively address the concerns of youngsters?

several campaigns have been undertaken by the Chinese government and platform companies to “cleanse” the internet and promote “masculinity” to strengthen nationalistic pride. In this context, the contents about LGBTQ+ rights and gender diversity, which constitute an important aspect of CSE, are often termed as being against this agenda.

In the past decade, Chinese CSE educators have been proactively utilizing the internet and digital media to promote CSE. For example, as early as 2015, Marie Stopes’ China office (MSIC) started to transfer its CSE curriculum to digital and online platforms. Its online CSE course covers a wide range of issues such as sexual orientation and gender identities and expressions (SOGIE), gender equality, discrimination against people living with HIV, disability, and so on. More than 10,000 people have enrolled in MSIC’s free online CSE course. Meanwhile, the Sexuality Education Online Database created by Capital Normal University received more than 2.2 million hits as of by mid-February 2017. Wang Longxi, sexuality education project director of MSIC was invited to give a lecture on sexuality education at SELF (Science, Education, Life, Future) forum organized by the Chinese Academy of Science in December 2016. The video of his speech is the most viewed lecture at SELF. He was also part of a Beijing TV station program called “I am Speaker” in August 2016, where he talked about women’s rights and gender equality. Many CSE programs, researchers, and educators have set up accounts on influential online media platforms, such as Weibo and WeChat to disseminate information and reach out to audiences. For example, “sexuality”, the Chinese term for which is literally translated as ‘love and life’, is an account managed by Professor Liu Wenli, the leading CSE expert at Beijing Normal University, and “nurturing relationships” is a handle managed by an NGO dedicated to promote CSE for mentally disabled people, just to name a few.

However, these online spaces are vulnerable and volatile for CSE programs and educators for two main reasons. First, there’s the issue of censorship of content related to sexuality on the internet by the state and platform companies based on ideas that are moralistic and protectionist. Second, there’s competition among online content that aim to profit from marketizing and pornification of sexuality. This dual challenge necessitates CSE educators to continuously maneuver and negotiate these spaces by adapting their content and strategies.

To further analyze these issues, we interviewed three Chinese sexuality education experts, who elaborated on the characteristics and challenges they face in the digital era, the various strategies and methods they apply while conducting CSE programs to meet the needs of young people, their parents, sexuality educators, and raise awareness among the general public on the importance of sexuality education for children and youth. Professor Liu Wenli from Beijing Normal University is of the view that since digitalization is a result of development, there are no measures or policies that can effectively prevent children from using the internet to obtain information. “If sexuality education is not carried out at home or school, the information and knowledge on sex or sexual behavior obtained through the internet may be unscientific, inaccurate, and biased, which will negatively affect the sexual norms and behavior of the younger generation,” says Professor Wenli. She also believes that it’s high time for sexuality educators to reach out to youngsters through digital platforms. “I think I should use the internet to make myself an influencer. I can influence the younger generation by publishing more evidence-based information and non-biased opinions as vlogs. Access to sexuality education is the right of young people. Using the internet and new information and communication technologies to obtain this information is their right to education. In addition, it is important to make policies with the perspective of children’s rights instead of prohibiting sexuality education in the name of protecting them,” she adds.

Notably, Professor Wenli has become a very influential sexuality education expert in China with many followers on Weibo, WeChat, Baidu, and some video platforms. However, she says that one of the biggest challenges is to convince men to receive sexuality education because people misunderstand sexuality education to be a way to teach girls to protect themselves from sexual violence and abuse.

Furthermore, several critical topics in CSE, such as homosexuality, sexual orientation and gender identities, diversity and human rights, etc., are still highly sensitive and constantly censored, flagged for supervision or blocked by platform companies and government authorities. The challenge for CSE educators is thus, the lack of transparency and how these platform companies actually censor these issues, what laws and policies is their censorship based on, how their algorithms work, and so on. This non-transparency and the imbalance in power relation makes it nearly impossible for users to bargain or appeal with the companies when their accounts are suspended, deleted or their content is removed. To avoid this, they self-censor the information they post on the platforms.

In addition to regulation and censorship, CSE programs also face the challenge of commercialization and marketization of sex and sexuality. Wang Longxi, former director of sexuality education project at MSIC, points out that non-profit organizations and commercial companies adopt different approaches to sexuality education. “The controversial nature of sexuality-related topics makes sex a selling point. On the internet, topics such as sexual pleasure, violence, sadomasochism (SM), and pick-up art (PUA) can all be monetized, so, profit-seeking companies see this as a business opportunity. They advertise on the internet and attract huge number of paid users and such ‘sexy’ information can go viral. However, users find it difficult to identify the quality of the content or verify the accuracy of the information,” says Longxi. Despite the progress made in digitalizing CSE courses, they are hardly able to compete in the market.

It is to be noted that the recent years have witnessed a rise in youth leadership in the field of sex education, which has furthered the cause of CSE online. Youngsters have established and managed their social media accounts as CSE platforms, publishing articles, producing vlogs, offering training for trainers, and participating in public debates. The emergence of youth leadership and opinion leaders in the realm of sexuality education is representative of the current digital age.

Meanwhile, Professor Gou Ping from Cheng Du University, another leading figure in CSE in China, is of the view that online CSE programs cannot change the behaviors of youngsters. “While online education is indeed convenient and efficient in terms of popularizing sexuality education, it is difficult to achieve the ultimate goal of CSE programs through online education. The ultimate goal of these programs is to change the norms and behaviors, as well as to respond to the confusion and problems of individual students.” This is because self-learning curriculums often lack interaction, and are not able to address or immediately answer the questions that some students may have. “If students have unanswered questions, how can we expect them to handle intimacy in relationships later on?” Professor Ping asks. She believes that the pedagogy of CSE, which places emphasis on respect, diversity, and empowerment for students is as important as the content of CSE which focuses on the triad of knowledge, behavior, and skill.

Conclusion

Currently, the primary channel for Chinese youth to obtain information about sexuality is not through formal school curricula but the internet and traditional mass media. Both these avenues are prone to hosting non-scientific information, gender-based violence, bias, discrimination, stereotypes, etc. The information and values conveyed in these media influence the sexual norms and conduct of youth. CSE educators and advocates have started using the internet and social media proactively to promote CSE. But they are wary of the effectiveness of online sexuality education, given the vulnerability and volatility of the online space due to censorship and non-transparent policies of platform companies. Aside from using platforms such as Baidu Encyclopedia (Chinese version of Wikipedia), vlogs, WeChat, etc., CSE educators have also built and use their own websites. They also use social media and online meetings applications to disseminate knowledge and concepts about sexuality, since they can reach out to more audiences when compared to traditional classroom settings, including out-of-school youth, parents, and the general public.

However, there are concerns on the limitation of online CSE programs and initiatives. Although, online lectures can reach diverse audiences, they lack interaction and engagement with the audience and youth participation, which is one of the most important principles of CSE. Thus, offline curriculum cannot be replaced by online CSE programs.

Moreover, online spaces are highly contested. Recently, several campaigns have been undertaken by the Chinese government and platform companies to “cleanse” the internet and promote “masculinity” to strengthen nationalistic pride. In this context, the contents about LGBTQ+ rights and gender diversity, which constitute an important aspect of CSE, are often termed as being against this agenda by “feminizing” and “disempowering” the nation. Additionally, CSE educators and advocates are often exposed to online hate speech and misogyny. Meanwhile, the commodification and marketization of sexuality and bodies has attracted investment from corporate powers who are trying to capitalize this lucrative field. This should be juxtaposed with the fact that CSE educators lack financial resources to conduct online CSE programs.

So, what space is left for feminist advocates in this arena? How can feminists claim their autonomy in a space pervaded by such power dynamics? One way of doing this is to build youth leadership, including young feminist leadership in the field of CSE. Young feminist activists and youth CSE peer educators have provided their valuable experiences in this struggle, especially on online media platforms, which continue to be the most important venue for their interaction with CSE. In addition, we need to strengthen feminist analysis on state regulation and marketization of bodies and sexuality in the digital era, to disrupt the tripartite relationship of toxic masculinity, parochial nationalism, and heteronormative ideology that demonize and delegitimize CSE and feminist politics. Feminists should also collaborate with other individuals and groups that work on issues of social justice, to demand transparency and accountability in internet governance, and equal participation in policymaking processes.

The authors would like to thank Liu Wenli, Gou Ping, and Wang Longxi for their precious time and insights for this essay.

This is the twelfth piece from our special issue on Feminist Re-imagining of Platform Planet.